This article was originally published on March 8, 2014.

Recent op-eds have labeled Putin as a mastermind or a megalomaniac fool. I am of the opinion that Putin is a megalomaniac mastermind exploiting a disempowered US. However, debating Putin’s psychological profile is less constructive than analyzing the economic foundation of his regime. Putin and his Russia survive on energy revenues, and war is only making him richer. Unlike 2008, when Putin invaded Georgia, oil prices have held steady. In fact, the threat of sanctions on Russia have only driven oil prices marginally higher, up $2 dollars to $110.8/bbl as of writing. Putin is financing expansionist dreams (and his own savings account) thanks to his near-monopoly on Russia’s energy industry. Therefore, the best way to rein him in is to drive global energy prices down. The US can accomplish this quite easily with a reformed national energy policy. Currently, the US is sitting on an unused 727-million-barrel underground cache of crude oil, and is producing more and more natural gas by the day. If the US were to supplant Russia as Europe’s primary natural gas provider, and flood the global market with American oil exports, energy prices would plummet. A decrease from $110/bbl to $80/bbl would cost the Russian oil industry alone an estimated $120 billion, plus billions more in foreign exchange earnings. Putin is a deft leader, but even he could not survive such a sustained economic collapse.

Russia’s move to deploy soldiers in Ukraine is indicative of feelings of insecurity rather than confidence. Putin knows that such a large loss of influence in Ukraine, a critically important country in economic, cultural, and geopolitical terms, would be devastating to Russia’s ultimate goal of increasing its regional sphere of influence and international prestige. Putin’s domestic considerations and tensions can also shed light on these aggressive actions. If a small country like Ukraine can successfully stand up to the Kremlin by ousting its man from Kiev, what will Russians think of a leadership unable to control their “Small Russia?” Russia is acting out of desperation, not strength. Putin’s clownish justifications for Russia’s military actions do not hold up to scrutiny and are made under a façade by what I recently labeled an “imitation democracy.”

While the West has multilaterally condemned this act of aggression, which is a positive first step, it should now increase pressure on Russia to relent. In order to force Russia to withdraw and accept Ukraine’s sovereignty and a chance at a peaceful political transition, the West must maintain a multilateral and wide-ranging coalition of rejection, isolating Putin via sanctions on both his allies and competing oligarchs (including their overseas funds and visas), and by supporting Ukraine’s new government through assistance and advisement. At this point, conventional military power projection against Russia is not a viable option – no matter how tempting – as it could spark an unintended military provocation leading to conflict. The current situation is very difficult to manage, although the international community should know that the West ultimately has the upper hand. Russia’s desperate authoritarian strategy based on oppression is doomed to fail in the long-run.

The situation in Crimea is nothing more than the Russians managing their own geopolitical periphery, and so far as it has to do anything at all with expansion, it is only due to the fact that Russian power is presently contracted to levels far below what Moscow would like. America would do and has done the same thing in the event of revolutionary unrest in our neighbor states, as is evidenced by our interventions in Mexico a century ago and in Cuba a half-century ago.

The question here, I think, is what the United States is going to do about it. Part of our grand strategy since the end of the Cold War has been to keep the Russians from establishing formal or informal dominion over the former U.S.S.R. Another part has been supporting the thin veil of liberal international order that girds the power politics flowing subtly underneath in an effort to at least grant a semblance of order and harmony in international affairs. These imperatives have come under increasing pressure in recent years, but in 2013 and 2014 more than ever before. I don’t know what the proper policy response should be, but I hope it isn’t more of the lectures, gestures, and silences with which President Obama responded to the Russians in the Snowden and Syria affairs.

America is in no position to intervene nor should it. To the western world, Putin’s actions appear nefarious, but from the perspective of many Russians he is acting well within the parameters of international law. Professor Tatiana Akishina of USC argues that, since the prime minister of Ukraine’s semi-autonomous Crimea region has called upon Putin for military support, his intervention is in accordance with international law. Moreover, America has intervened with greater frequency and intensity over the past century, thus it is highly hypocritical of US authorities to castigate Russia for meddling within its region. That being said, it is somewhat disturbing to witness Russia fail to respect the sovereign rights of an independent nation. One can only hope that Putin’s intervention into the region will be short lived.

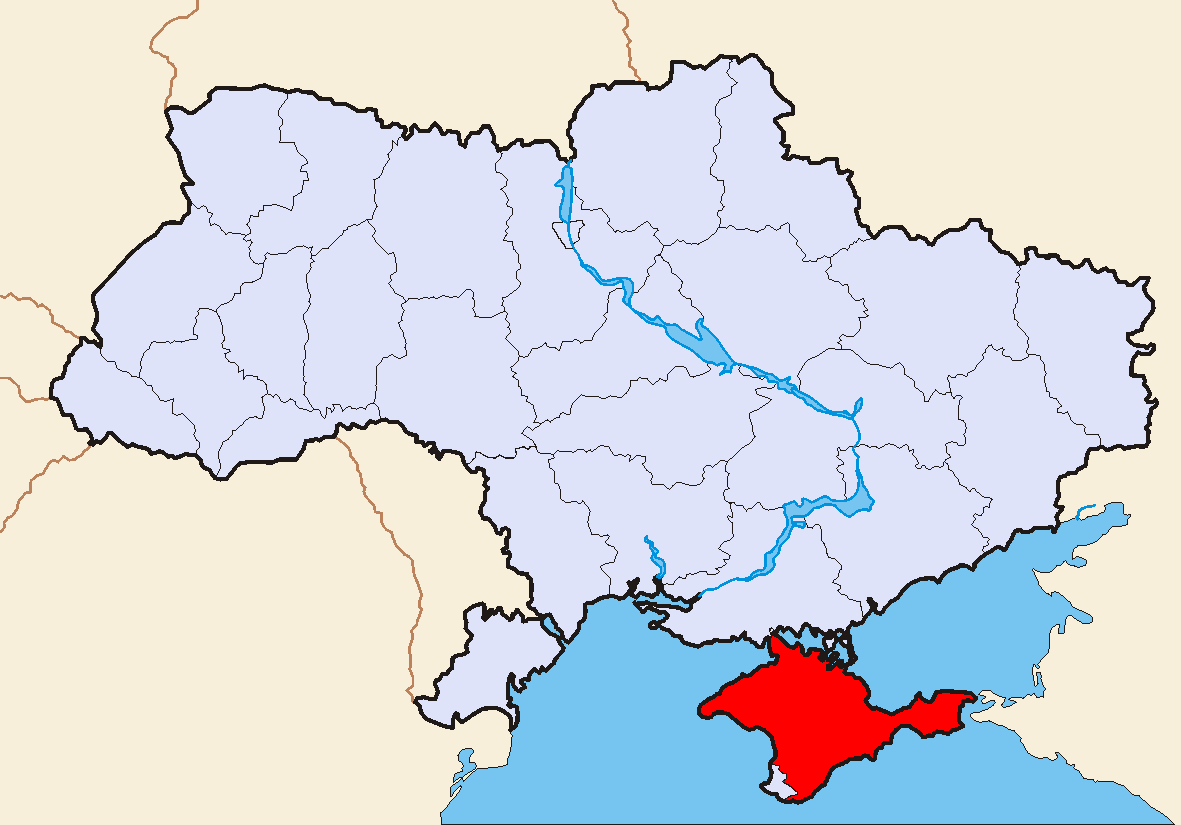

There is a risk of ethnic cleansing. It starts with classification. Weeks before this conflict made the front pages of the New York Times, reports emerged that Russian-Ukrainians in Crimea were being given Russian Passports. Russians have lived in Crimea for some 200 years, and Ukraine has held the territory for half a century. Then there are the Tatars, the people for whom Crimea is an ancestral home dating back to the Mongol Khan Empire. The Tatar population, which accounts for 13% of Crimea’s inhabitants, is predominantly Sunni Muslim. Under Stalin’s Russia, the Tatars were accused of collaborating with Nazi Germany and deported en masse to other parts of Russia (read: Siberia). It should come as no surprise then that they are more keen on being governed by Ukraine than by Russia. As things stand, there are three populations with strong ethno-nationalist tendencies who inhabit a geographic area they all feel they have a historical, political, or legal claim to. Of the eight stages of Genocide, we’ve passed #5: polarization. That means preparation, extermination, and denial are next.

Sabrina Mateen

Before this conflict, my knowledge of Ukraine consisted solely of “ex-USSR”. I assumed the region consisted of Russian natives, and that they were considered to be allies with their ex-country. However, with the news of an outbreak of civil war, it has become apparent that there are opposing nationalities, languages, and mindsets that are all helping to tear Ukraine into pieces. The conflict seems to be reaching increasingly dangerous heights as Russia begins to put pressure on Ukraine in the form of planned military drills and in one case, an unspecified military presence that looked to be Russians supporting Crimeans. Although the conflict is being called a civil war, it is beginning to seem like one of the many moves Putin has been making to restore Russia to its USSR-era square footage. It is important to see what the United States plans to do, as the Obama Administration is already under scrutiny after the ill-advised response to the crisis in Syria. Any move from the newly war-shy United States will be seen as an escalation in a conflict that has all the makings of a new Cold War.

Recent developments in the volatile Ukraine situation show the autonomous Crimea region voting to join the Russian Federation. Crimea has a Russian ethnic majority and is predominantly Russian speaking, so it might not come as a surprise that the region is in support of the secession. If it is what the people want, then perhaps the region should have never been a part of Ukraine to begin with. These recent moves that Crimea has made are violations of international law, which puts the United States in a tough response position. The President has been making frantic calls to Putin urging a diplomatic end to this crisis, but to no avail. Meanwhile, Putin doesn’t seem particularly concerned with US warnings. What the EU and the US bring to the table are economic sanctions, and it will be interesting to see if those “sticks” are enough to make Putin falter.