In the middle of the coronavirus pandemic — just as the United States passed 1 million cases — President Donald Trump announced the U.S.’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization. During a press conference in the Rose Garden in late May, Trump accused the WHO of failing to adequately inform the world of the then-impending pandemic and accused the organization of bending to the political will of China.

“China has total control over the World Health Organization,” Trump said.

While the president’s claim was dubious, the decision on part of the administration was made. However, to fully understand the extent to which the U.S.’ departure will impact the organization’s strength and the effectiveness of the world’s pandemic response, it is important to analyze what it means to leave an international organization like the WHO.

During his address, Trump blamed China for instigating the pandemic — yet, not once did he mention the U.S.’ responsibility for the death of thousands of Americans. The decision was met with backlash from health experts and public officials.

Dr. Howard Koh, former assistant secretary for health during the Obama Administration and current professor at Harvard University’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health, called the decision “short-sighted and ill-advised” in a quote to NPR. “All [this decision]does it put American lives at risk,” he said.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said he first heard about the decision to leave the organization and halt American funding through the president’s press conference. The decision to terminate the U.S. relationship to the WHO came only a few weeks after President Trump sent a letter to Tedros, in which he claimed that the organization favored China and needed to make reforms within 30 days.

“The U.S. government’s and its people’s contribution and generosity toward global health over many decades has been immense, and it has made a great difference in public health all around the world.” Tedros said. “It is WHO’s wish for this collaboration to continue.”

Since its inception in 1948, the U.S. has been a foundational member of the WHO, a specialized United Nations agency headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. The organization’s founding constitution outlines its principles and main objective, which is to strive for the highest level of health of all people. The U.S. has since played a major role in its operations, and has consistently served as the organization’s top benefactor — providing around $400 million each year, or 14% of the agency’s funding.

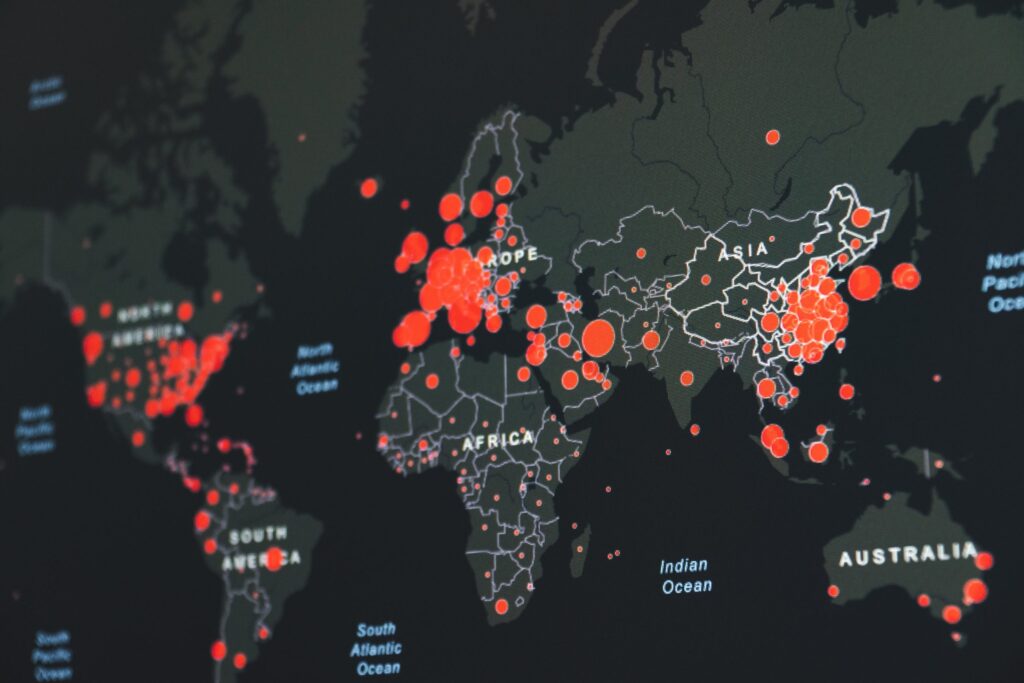

Historically, the organization’s broad mandate has been critical to global health achievements, including the eradication of smallpox, the fight against polio and the creation, development and distribution of the Ebola vaccine. Amid the current coronavirus pandemic, the WHO has played a key role in coordinating an international response to the outbreak and providing important information and developments across the globe. Though the U.S. helped found the WHO, it is now is turning its back to the organization, during one of the most important times in the body’s recent history.

But, the decision remains uncertain, and it’s questionable whether the President is allowed to make the decision of withdrawing from the WHO. Part of its uncertainty is the question of whether or not the decision is an overreach of constitutional powers and if the unilateral decision needed congressional approval.

Additionally, according to the Congressional joint resolution that brought the U.S. into the WHO, U.S. law dictates that the country must give the organization a year’s notice and must see through its financial obligations for the current year: 2020-2021. Though the American president has the right to withdraw from treaties, there is no specific provision in the WHO’s constitution for how a member ought to leave the organization.

If the WHO does need 12 months notice, however, it is further unclear who will be making that decision. Until November 4, the victor of the presidential election is unknown. If this is the case, Trump might not be president and his successor will have the ability to revoke the decision.

Regardless, Trump’s decision ultimately means that the WHO loses nearly $1 billion in contributions every two years, resulting in unforeseen consequences for public health and international cooperation. Trump said the U.S. would be “redirecting those funds to other worldwide and deserving urgent global public health needs;” though it is unknown what other public health concerns are being referenced.

While the legality of this decision is unclear, Trump’s rhetoric regarding the WHO has been irrevocably damaging. As the U.S. navigates this quick decision and as the 2020 presidential election nears, new funding negotiations at the WHO have been placed on hold. Imre Hollo, director of planning, resource coordination and performance monitoring for the WHO, told Time that the organization anticipates a funding gap and is currently experiencing financial freezes.

Trump’s attitude toward the WHO has also weakened the U.S. as a face of international cooperation and global leadership. This result is unsurprising, as the current administration has rolled back many existing partnerships and treaties formerly established — for example: the U.S.’ withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Council and from the Paris Climate Accords.

But what is seemingly most damaging about this decision is that it seems directly in contradiction with Trump’s claims for leaving the WHO in the first place. If Donald Trump fears that the U.S. has less leveraging power in the body than China, then leaving the organization might exacerbate the problem.

In the wake of the coronavirus’s spread throughout China, the Chinese Communist Party has ramped up efforts to restore the country’s image and has increased disinformation efforts to combat the narrative that the government botched its response to the pandemic. Since the start of 2020, China deliberately spread misinformation campaigns related to its handling of the virus and the timeline of the outbreak. Throughout January, the WHO publicly spoke about China’s response to the seemingly-contained virus and praised the country for its swift response. However, this public commendation was coupled with internal frustration with China’s inability to share accurate and sizable information with the WHO on the spread of the daily virus.

That being said, the WHO took action in January, declaring the pandemic a global emergency and warning of person-to-person transmission. While the WHO sounded the international alarms, President Trump continued to downplay the severity of the threat — a reaction that has led to the damning and lethal impact of the virus on the U.S. today.

Leaving the WHO means the U.S. formally loses its seat at the table when handling issues of global concern and public health. This decision gives China a more powerful position in the WHO, simply because of the U.S.’ absence. If the U.S. wants a better shot at tackling the current and future pandemics — which have the potential to be greater in magnitude and worse in effect — then President Trump, or whichever administration takes hold in November 2020, ought to reconsider this decision.

Ultimately, the WHO, like many international bodies, has significant room for improvement. Its response time, efficacy and will to act must improve to better tackle public health disasters, but leaving the WHO all together is more damaging than working to improve it. The U.S.’ relationship with the WHO should not be a matter of personal or political ego, but rather a life or death decision for the thousands of people, industries and economies across the world that have suffered at the hands of the virus.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.