Let’s play a game of word association. What do you think of when you hear the word British? Could it be the late Queen Elizabeth II? Perhaps tea and crumpets? Or is it the picture of a well-dressed gentleman wearing monocles and speaking in perfect Queen’s English? In reality, the meaning of “British” is beyond these stereotypes, and it is starting to change as British popular culture undergoes a revolution.

Once the largest colonial empire in the world, the United Kingdom once owned territories from Pakistan to Jamaica, projecting its political and cultural influences upon its colonies. After World War II, Britain gradually renounced its colonial possessions, sprouting the creation of new states across Africa, Asia and the Caribbeans.

In search of better economic opportunities, immigrants from former colonies began to move into British cities. In 1948, the ship HMT Empire Windrush brought a group of 800 Afro-Caribbean migrants to the port of Tilbury; thus, the wave of Caribbean immigrants is named the “Windrush Generation.” The arrival of Windrush passengers seven decades ago became an iconic moment in British history, marking the beginning of a multicultural Britain.

As immigrants found new homes in the British Isles, they brought over their distinct and different cultures and traditions. Developed by Bangladeshi immigrants in the 60s, chicken tikka masala became the United Kingdom’s national dish and is beloved worldwide.

Curry houses and chicken shops —- both immigrant inventions —- are widely popular across the United Kingdom, and as such cultural phenomenons became integral to British society. Islam became the second largest religion (3.3 million Muslims) and the fastest-growing religion in the United Kingdom (2.7% in 2001 to 4.4% in 2011), with over 100,000 converts to Islam. In 2019, a record number of 19 Muslim MPs were elected, and the first Muslim mayor of London was appointed three years prior.

The new generation of immigrants is mainly born and raised in the United Kingdom and, for the most part, speaks English as their first language. As their parents and grandparents struggled to integrate into British society and build stable foundations for their children, the new generation became the torch-bearers of their elders’ legacy with their renewed abilities to make a cultural impact upon British society.

Emerging from the streets of 1980s London, the Multicultural London English (MLE) dialect soon made its way across the country. It was a new dialect rooted in Cockney but heavily influenced by Jamaican patois from Jamaican communities in London, where young and multiethnic societies adopted this new tongue. As young people from different immigrant communities interacted, different words and phrases from other languages were added into the mix.

Nowadays, the MLE dialect has become a trademark of urban London culture, as it is a living and breathing example of the ever-evolving pop culture scene of the United Kingdom and a true legacy of the Windrush Generation. However, this reasonably new cultural development faced backlash from commentators.

During a BBC program, historian David Starkey commented, “The whites have become black…Black and white, boy and girl operate in this language together. This language which is wholly false is a Jamaican patois, that’s been intruded in England and this is why so many of us have this sense of literally a foreign country.”

Language is fluid and ever-changing, where new phrases reflect upon a place’s societal development and change. The versatility of MLE and its ability to connect and relate to youths of different backgrounds exemplify the evolutionary nature of language.

This phenomenon of language contact is relatively common amongst modern multicultural communities, where two or more languages interact and influence each other, creating new idioms and popular phrases. This phenomenon is not just in the United Kingdom. Urban environments all over the globe have also undergone linguistic changes, with examples like the Arabic influence in French and the usage of Turkish slang by Berliners.

With the linguistic transformation in urban British society, the music scene of the United Kingdom is, in turn, revolutionaized by trailblazing artists with immigrant backgrounds. One of the United Kingdom’s most popular genres of music was grime, a real-life testament to a homegrown British cultural product synthesising genres from former British colonies, most notably from the Caribbeans.

To “de-Americanize” hip-hop music in the United Kingdom, trailblazers of the genre sought to develop a distinctive sound that highlighted what British pop culture was like at the time. Interestingly, the Guardian describes the genre as “post-punk angst on wax—a heady mix of dancehall, jungle and United Kingdom garage, inspired by Jamaican ragga toasting and the storytelling of US hip-hop.”

Alongside the popularity of grime music, which put British artists with immigrant backgrounds and their experiences into the spotlight, the rise of the drill genre since the start of the 2010s exemplifies the fluidity of culture in the 21st century. Drill music originated from Chicago, yet it had made its way into the studios of London, where the genre had swiftly taken over the country.

Characterised by a fast BPM and rather dark melodies, drill music appealed to younger and upcoming artists. In spite of the genre’s American origins, British artists could incorporate their specific experiences and lives into their tracks. U.K. drill sets itself apart with its intricate wordplay and unique references, which brought the renewed British urban culture to the rest of the world.

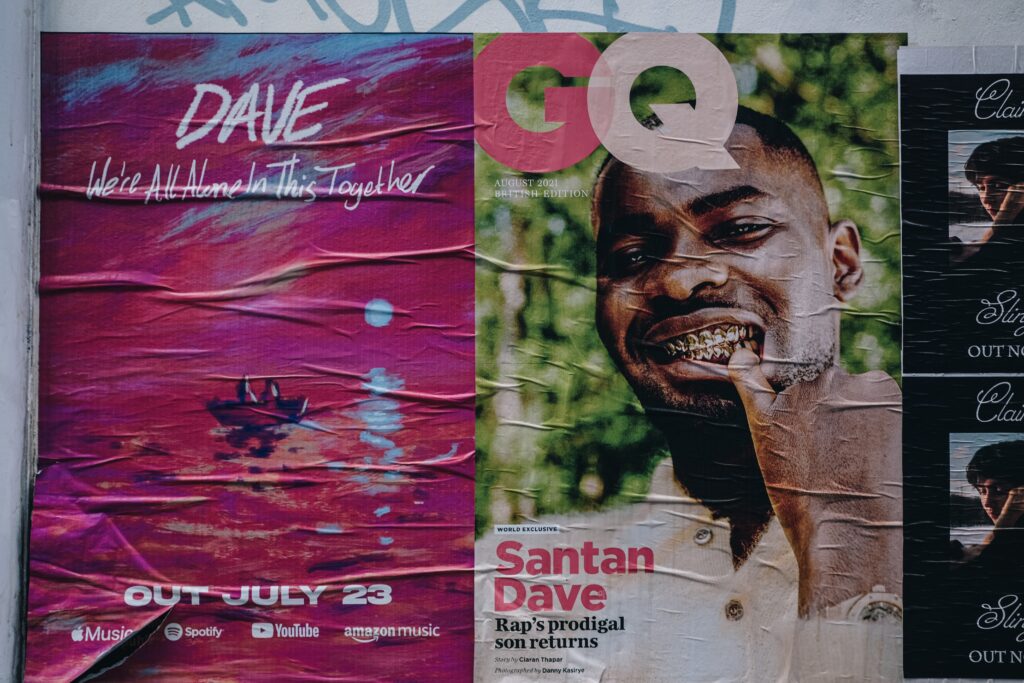

In a way, the rise of U.K. grime and drill brought attention to the British music scene. Artists like Central Cee, Skepta and Unknown T are known worldwide for their art, and youths worldwide (even in the US) sought to emulate their artistry. The popularity of British music genres signifies a brand new version of the United Kingdom, where different backgrounds and experiences can bloom and thrive as a part of the mainstream urban culture.

Coming from a Nigerian background, Skepta often employs cultural references in his tracks; his hit song “Greaze Mode” features the lyrics “I’m gonna need some palm wine, I’m gonna need some pepper soup,”referencing palm wine and pepper soup, both delicacies popular in Nigeria and other West African countries. Central Cee often features other immigrant artists from European countries, most notably from his track “Eurovision,” where he collaborated with Spanish, Italian and French artists with origins from countries like Algeria, Senegal and Morocco.

The new wave of British artists and genres exemplifies a rejuvenation of British cultural products, as immigrant artists inject a new sense of vibrance and appeal to British pop culture. The multitude of influences in the United Kingdom’s music scene shows the importance of decolonization, in which the brand new cultural relationship between the Global North and South signifies a new dynamic in terms of cultural influence. As an effect, cultural products with influence from post-colonial states around the world made its way into the mainstream of their former colonial masters, especially in the case of Britain.

In this new and spirited society, cultural products with Caribbean or African influences and roots are celebrated and popularized. Subsequently, youths from all backgrounds begin participating in such cultural phenomena, with those cultural products becoming the new mainstream of British pop culture.

Yet, the newfound popularity of fusion genres like grime and drill did come with controversy. Many have labeled drill music as a genre that glorifies and incites gang violence, where the explicit lyricism from drill tracks causes younger listeners to adopt dangerous lifestyles. In 2018, YouTube removed over 30 drill music videos as they were overtly violent.

In a way, the appeal of music genres like drill comes from its reflection of real-life experiences, where youths with immigrant backgrounds strive to survive in an often unforgiving and harsh environment. The new wave of British hip-hop encourages young artists to focus on their artistry and divert them from possibilities of gang violence. In the face of marginalization of immigrant communities, drill artists continue to defy the odds and carve out an important legacy in Britain’s cultural fabric.

Genres like drill dare to confront the bleak realities of life in suburban Britain, where such genres bring listeners with similar experiences and backgrounds together, creating messages that resonate with a broad group of people. As the U.K. music scene familiarizes itself with a wider variety of experiences, especially amongst crowds with immigrant backgrounds, it forms a new mainstream that reflects the demographic of modern Britain and speaks to a much wider audience.

As British pop culture evolved, the United Kingdom’s shifting cultural landscape brought a new mainstream, headlined by Brits with diverse backgrounds. The “cultural revolution” of British pop culture exemplifies the shedding of Britain’s old, as British society enters a new era where whiteness is no longer the norm.

At the end of the day, multiculturalism is what keeps British culture alive, where the sons and daughters of immigrants are now the beating heart of the United Kingdom’s cultural fabric. For the Brits and its culture to thrive amongst the world, its heart shall keep beating as long as it can.