The science is clear. 1.5°C warming from pre-industrial levels keeps the impacts of climate change at a manageable level for the global community. For the Global South nothing short of this temperature increase is acceptable. This aspirational goal of 1.5°C was agreed upon in the legally-binding Paris Agreement which was signed by 196 countries. Since this Conference of Parties (COP) in 2016, little tangible progress has been made despite the pleas of climate activists around the world. Similarly, this year’s COP was filled with urges from civil society, but it concluded this Sunday with a groundbreaking effort in terms of climate justice while also backsliding on a fossil fuel phase-out.

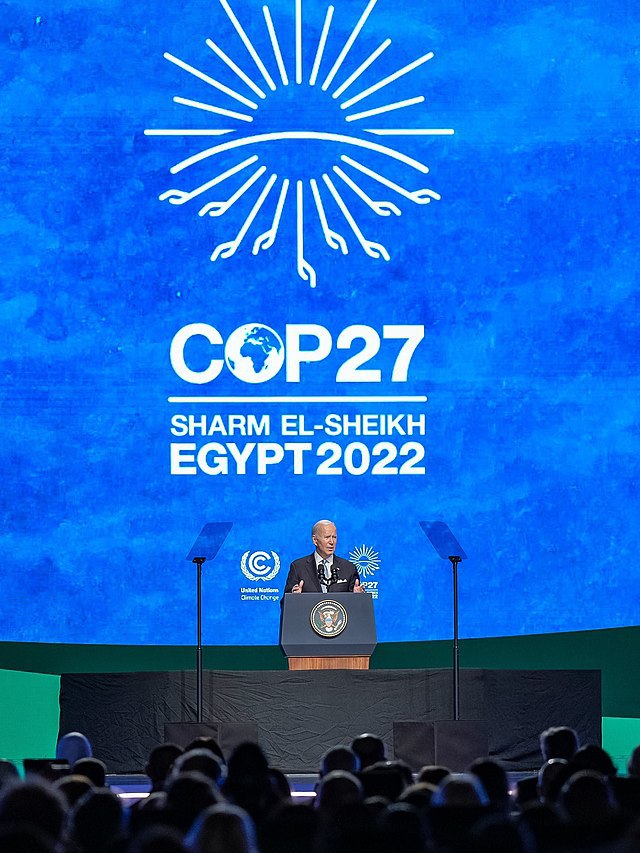

Throughout COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, indigenous peoples, politicians from the Global South and climate activists faced systemic repression ranging from large-scale arrests, limited transportation, no interpreters for events, etc. As these groups called for reforms by the Global North, their voices appeared to fall on deaf ears while politicians from the United States, the EU, Canada and more pushed alternatives such as green hydrogen as the way of the future as opposed to a full phase-out of fossil fuels.

From the beginning of week one, the United States remained firm on its position to not add finances to an additional loss and damage fund, which was a non-negotiable matter for the G-77 and China. As a result, at one point during the talks, these countries suggested they were willing to walk out if such finances were not provided, and while the countries continued to negotiate this issue, due to a lack of consensus, the talks were extended by two additional days. It was in this short extension time that everything drastically shifted.

On Saturday morning, the talks “appeared close to collapse.” Beyond the unresolved issue of a loss and damage fund, debates surrounding clear language on a fossil fuel phase-out and even the inclusion of language surrounding human rights remained. However, the unity of the Global South and civil society positively influenced the final outcomes of negotiations and pushed for an agreed upon resolution that included elements of climate justice. As a result of the outcome, many individuals, such as Ephraim Mwepya Shitima, the chairman of the African Group of Negotiators noted how they “’will be going back smiling’” because the final resolution passed in COP27, the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, “’is a victory, not only for Africa, but for developing nations.’”

The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan makes tremendous strides in addressing a just transition into renewable energy by recognizing “the important role of indigenous peoples, local communities, cities and civil society, including youth and children, in addressing and responding to climate change.” The resolution also places an emphasis on “common but differentiated responsibilities” and acknowledges the significance of both the cryosphere and oceans when combating the climate crisis. Beyond these efforts to ensure an “equitable transition,” one of the most important elements of the Implementation Plan is the fact that it includes the highly contested loss and damage fund. The resolution ensures that the Global North will establish a fund for those “particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.”

The plan also “[r]esolves to pursue further efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5*C,” yet regardless of this effort and the progress in the realm of climate justice, many scholars have argued that there was actually backsliding on the question of fossil fuel phase-down. In Article 4.13, rather than arguing for a complete phase-out of coal and all other fossil fuels, the text calls for a “phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.” Therefore, there is no concrete language to firmly address the driver of climate change – fossil fuels.

Similar to how civil society and the Global South pushed for a loss and damage fund along with a just transition, the fossil fuel delegation, one of the largest groups at the COP numbering at 636, pushed their own agenda. The efforts of the fossil fuel delegation, which increased 25% from last year, effectively worked with oil-producing states such as Saudi Arabia to limit the mention of fossil fuels. As a result, the executive vice president of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans highlights how the final resolution, “puts unnecessary barriers in the way and allows the parties to shy away from their responsibilities.”

Overall, there are many outcomes from COP27, but one of the most significant is the progress made in terms of climate justice. For the first time, there are concrete steps to establishing a loss and damage fund for the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Yet, there remain many concerns as to the true efficacy of the COP process. As thousands gather from around the world, many of the most powerful decision-makers on privately chartered flights, there remains continued co-optation and repression from the voices most affected by the issue. In contrast, the fossil fuel industry remains one of the most influential delegations, despite their inherent conflict of interest, and they directly impacted the results of COP27. However, given the tumultuous history of the international climate regime and the tangible process that was established in COP27, Sharm el-Sheikh can be largely viewed in a positive light.

Next year, COP28 will be held in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates which will present additional challenges beyond those of Egypt. Questions as to the further repression of civil society have already been raised, and discussions about increased accessibility remain to be seen. But after two weeks of hostile negotiations, an agreed-upon Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan that includes a loss and damage fund and has kept the hopes of 1.5°C still alive is a welcomed outcome.