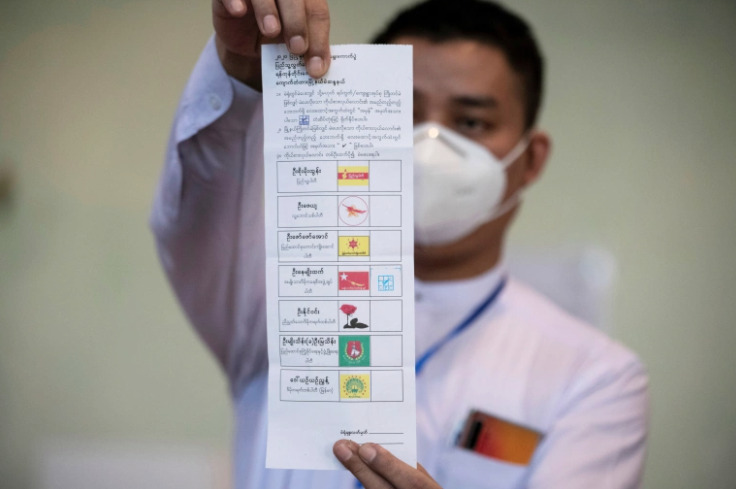

As Americans watched in anticipation of their 2020 presidential election results, Myanmar held its own national election on Sunday, November 8. This is Myanmar’s second election since the military relinquished control in 2011, and this referendum solidified the power of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD). Suu Kyi’s party secured 397 seats out of 664 in Myanmar’s parliament, an even greater landslide than their victory in 2015.

The results come amid increased tensions within the country, particularly over the NLD-led government’s mistreatment of ethnic minorities. Aung San Suu Kyi herself, over the past five years, has gone from a “human rights icon” to an “international pariah” for defending the military’s violence against the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic group in western Myanmar. The 2020 elections, although considered the first “fair and free” in decades, are symbolic of a return to authoritarianism in the country.

The elections did give rise to numerous young, independent candidates, but the NLD, as the dominating force in Burmese politics, has used its power to silence critics. Despite its origin as the democratic opposition to the military, the government has arrested hundreds of politicians and citizens for expressing opposing political views. The party has also usurped control of the media by cracking down on free press and allowing for the censorship of rival party websites.

Most significantly, the government excluded the votes of more than 1.5 million people, citing security concerns. The NLD canceled elections in over 50 townships, subsequently suppressing votes across ethnic constituencies and forbidding minorities like the Rohingya from participating in the election. Andrew Ngun Cung Lian, a Burmese constitutional scholar, remarked that “[i]n some ethnic areas, people are very hostile to the NLD and support ethnic parties instead… It feels like the NLD took advantage of the fighting to silence ethnic people.”

Ethnic minority groups make up nearly one-third of Myanmar’s population. About 600,000 people are part of the Rohingya community, who have suffered brutal persecution by the military, ranging from gang rape to forced labor village burnings. Although the Rohingya had faced violence and persecution in other respects for years, they were previously able to vote and run in all elections.

However, this year, the Rohingya were denied their right to vote, despite orders from the International Court of Justice and calls from international human rights groups. According to Wai Wai Nu, an activist of Rohingya origin and Executive Director of the Women’s Peace Network, “[t]he Aung San Suu Kyi government has shown no political will to restore Rohingya’s rights in Myanmar”. Although Suu Kyi’s party came into power in 2015 motivated to bring democracy to the country, the government has institutionalized the discrimination of the Rohingya and the military continues to enjoy impunity as the violence worsens.

The military’s abuse of the Rohingya people has been met with intense condemnation from the West. Suu Kyi’s refusal to condemn the ethnic cleansing and her defense at the International Court of Justice in 2018 has led international governments to withdraw their awards and keys to their cities. Bill Richardson, the former American ambassador to the UN under President Bill Clinton and a longtime ally of Aung San Suu Kyi, highlighted the irony of “the international community us[ing]its liberty to promote hers [while]she is using some of the very same legal mechanisms as the military to stifle freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly.”

In late 2019, the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced it was investigating alleged human rights violations against the Rohingya as a possible case of genocide. This is a landmark move for the international community – a significant step in holding Myanmar accountable and bringing justice for the victims. The West’s greatest challenge is taking a tough stance against the persecution of the Rohingya without reinforcing Myanmar’s democratic weakening. Nevertheless, the worsening conflict and the government’s indifference have Western businesses and politicians thinking twice about their presence in the country.

Myanmar, which had long adopted a “neutralist foreign policy” since the country’s constitution in 1974, may have to search for allies elsewhere as Western support dwindles. China seems to be the most natural choice, although handling China has proven more and more difficult for the Burmese government.

Not only are China and Myanmar connected by a 2,200 km shared border, but also through China’s ties to ethnic armed groups that control outlying regions of the country. There is generally a negative public opinion towards China among Burmese citizens, and even the Myanmar government and military have worries about China’s growing influence. Yet, it seems unlikely that the NLD will take any significant steps to limit Beijing’s engagement, given Myanmar’s worsening relationship with the West and the necessity of Chinese support for the NLD’s domestic objectives. The NLD relies on Chinese investment and infrastructure funding to spur economic growth and needs China’s political clout to forge peace in the borderlines.

The next five years of NLD will see Myanmar pursuing an “independent and active foreign policy” by relying on Chinese support while also gradually offsetting their growing influence. Myanmar will look to strengthen ties with other regional partners like India, Japan, Thailand, South Korea, and Singapore. Even so, without Western support, weaning off an “unhealthy reliance” on China is unlikely.

The NLD remains popular among the country’s mostly Buddhist ethnic majority group, the Bamar, which still views the party as the only bulwark against military absolutism. However, the government has created a climate of repression in the country that may bring about its own downfall. Heading into their second term, unless the government ends its suppressive practices and takes a stance against the military’s persecution of the Rohingya, the future of democracy in Myanmar looks grim.