In a well-researched article, Glimpse Staff Correspondent Katya Lopatko examines the nationalist movements bubbling up on both sides of the Atlantic, represented best by Donald Trump, Brexit and the far-right parties gaining a following across Europe. Without making any particularly sweeping statements or claims, Lopatko pretty fairly documents the “Isolationist” phenomenon as it relates to international integration, immigration, trade and other issues.

In my opinion, though, there are two interrelated themes Lopatko’s reporting misses, their absence evidenced in her conclusory depiction of resistance to globalization as “understandable, but ultimately futile.”

First, the notion that there is a class divide between elites and commoners in the debate over globalization; and second, the notion that globalization is not an inevitable process, but in some ways is a set of policies states can choose or not choose to make (and, being a set of policies, is a project that can fail or succeed). We will examine these two contentions in turn.

Globalization and the Class Divide

Various scholars and pundits, including my boss Joel Kotkin and the young New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, have opined something which I believe future historians will take for granted as a basic fact of the early 21st Century—namely, that there has risen an internationalist governing elite across the Western world. This elite tends to be buttressed by the educated professional industries, such as academia, law, finance and technology, and in its values it is solidly cosmopolitan and liberal. Take the economic interests and sociopolitical and cultural views of your average liberal arts graduate going into law or business, and mature them by thirty-five years or so and you’ve got Barack Obama, Angela Merkel and the recently-resigned David Cameron.

Meanwhile, as Kotkin and Douthat note, the vast working-class and middle-class majorities of these Western nations’ populations have directly contrary views and interests. By and large, they tend to be socially more traditionalist and parochial, and their economic fortunes are more or less tied to industries such as manufacturing, energy, construction, shipping and agriculture. In normal political times these class-and-culture divides need not produce existential conflict; but in times of international upheaval and economic sluggishness (sound familiar?) class consciousness and class identity can easily come to dominate political debates in ways ideology only rarely does.

Traditionalist lower classes tied to physical industries, and cosmopolitan upper classes tied to knowledge-based industries. Take a guess—which is more likely to support increased global integration, multiculturalism, and free trade and immigration flows? Which is more likely to oppose them?

Globalization as Process, Globalization as Policy

The argument is sometimes made that globalization is basically a natural process, inherent to international trade and the resulting cross-cultural interaction. I don’t disagree; it seems to me that so long as you have an international economic order, as there has almost always been since Antiquity, you will have international supply chains and trading routes abetting cultural interaction and evolution. Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Zheng He witnessed this cosmopolitan empire of international commerce firsthand centuries ago; the technological booms of the last five centuries have only amplified the process. Railing against such inevitable progress, it would seem, is about as worthwhile as spitting in the wind.

This is all true—but at the same time, states and other polities retain significant power to react to the aforementioned globalizing trends. Aside from the basic pressure market forces put on states to modernize, there is no inevitable direction towards totally free international markets. Expanding states with productive industrial sectors tend to favor other states opening up their markets and buying their mass-produced goods; stagnant or declining states with less competitive industries tend to oppose openness for the sake of preserving their economic independence. Culturally homogeneous states feel threatened by greater openness, while culturally cosmopolitan states have no such scruples. Moreover, different social classes and ethnic groups within the same society, competing over control of the state apparatus, can have very different views on how a state should react to globalizing processes, resulting in seemingly incoherent compromises.

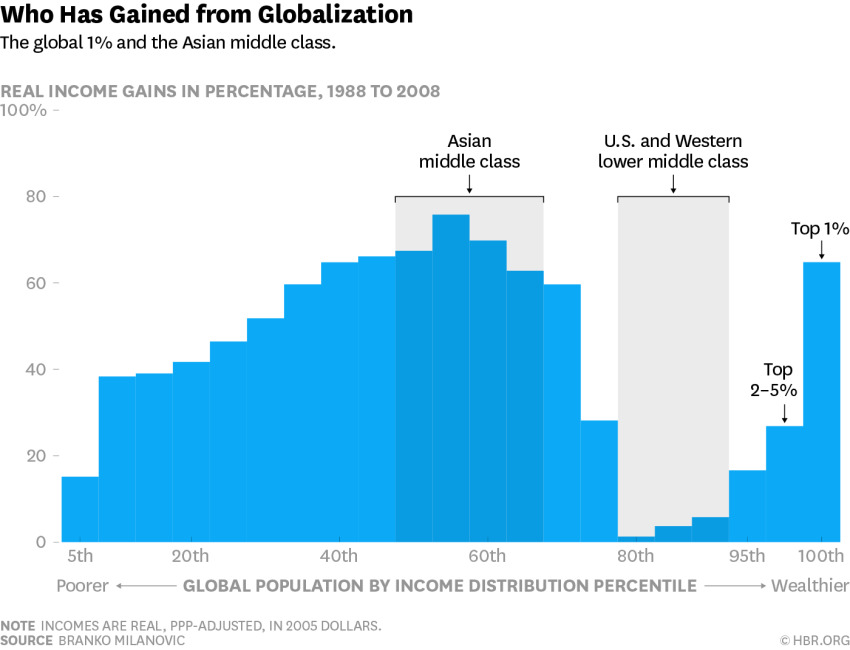

In the last thirty or forty years, the policy choices Western states made in reaction to globalization tended to smooth the cross-border flow of labor and capital, while weakening the coordinative economic power of the nation-state. This was by no means inevitable; export-oriented trade deals rather than free trade deals, high-skilled immigration quotas rather than mass acceptance of low-skilled workers, and other such policy alternatives have been pursued by developing powers – and incidentally, it is in these economically nationalist states in the developing world where middle-class and lower-class fortunes are rising, as opposed to in developed states where middle-class fortunes are stagnant. This chart by the historian Nils Gilman depicts the phenomenon.

It is primarily in Western Europe and the United States where internationalism of various sorts has replaced the hard-nosed nationalism being practiced elsewhere. The reassertion of national-interest realism in Western states could partially alleviate labor conditions, and if properly pursued, cultivate more international understanding in the long term than internationalist dreams of global integration and universal markets.

The neoliberal-internationalist policies of the last three decades or so—expansion of free trade, open-borders immigration, international financial deregulation, etc., coupled with the expansion of multilateral institutions- have made it harder for countries to control their own labor markets and industry, while making it easier for corporate entities to pursue their particular goals and interests across fluid borders without being subjected to crippling regulation. This segregation of political power and economic power at the highest levels has, of course, struck hard at Western publics’ self-images of self-determination and fed the plausible narrative that internationalist elites are not working in sync with the interests of their home nation. The weakened states are less able to provide security and stability for their angered citizenries, and the present wave of nationalist revolts follows.

The rise of radical ideologies at the beginning of the 20th Century in Europe was fed, in part, by the Romanov and Weimar elites’ inabilities to provide material and moral dignity for their peoples the way the English and Americans could. There’s something to be said for the stabilizing and pacifying nature of a strong and well-distributed national economy.

Lopatko seems to acknowledge that policy can champion or discourage the natural trends of globalization, but brushes aside the notion that nation-centric policies would be of any use in the world of the 21st Century. “Eventually, this [nationalist]approach will fall through and we will be forced to address problems that only intensify the longer we push them away.”

On this point, she and I strongly disagree.

Healthy Nationalism

The sentiments Lopatko reports on and labels “Isolationist” are indeed distasteful and vulgar to the cultivated sensibility. But they do not arise merely from hatred and racial supremacy on the part of lower-class boors at Trump rallies.

They are, rather, what happens when large groups of people feel disenfranchised and betrayed by their rulers, particularly on the question of national identity. When you delegitimize a people’s healthy, open, and reasonably inclusive national identity and replace it with something alien and unfamiliar, like multiculturalism or global cosmopolitanism, you pave the way for their embrace of far darker and more exclusivist expressions of national identity. It happened when “Frenchman” and “Briton” were replaced by “European,” and when “Americanism” was replaced by “Multiculturalism,” by the West’s cognitive ruling elites. Feeling that their true identities were under siege, the working-class traditionalist majorities of America and Europe turned to figures like Marine Le Pen and Donald Trump, who advocated returning to the “good old days,” and spouted a nationalism better described as ethno-nationalism or racial nationalism.

Ethno-nationalism, of course, is very different than the benign and inclusive nationalism peddled by figures like Franklin Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower. This form of liberal or civic nationalism tied to culture and language but unmoored to race emphasizes, simultaneously, racial equality and national distinction, seeking to bring diverse classes and ethnicities into a common assimilationist fold. It’s what Benjamin Disraeli spoke of when he referenced “one-nation conservatism” and what Theodore Roosevelt meant when he championed “100% Americanism.”

Though in the 19th Century this multiracial community was primarily limited to those of European descent (bear in mind Irish and Italians and Anglos were considered to be different races back then) some tried to bring the same model into the mid-20th Century and make it work between those of European, African, Latin, Asian, and other descents. This work informed some northern factions of the American Civil Rights movement. Its focus was reconciling and assimilating diverse groups into the national community—and that last word, community, is key. As Jonathan Haidt wrote in an essay for The American Interest magazine:

“Nationalists feel a bond with their country, and they believe that this bond imposes moral obligations both ways: Citizens have a duty to love and serve their country, and governments are duty bound to protect their own people. Governments should place their citizens interests above the interests of people in other countries.

…There is nothing necessarily racist or base about this arrangement or social contract. Having a shared sense of identity, norms, and history generally promotes trust.”

But healthy nationalism is more than simply a cultural phenomenon—for it to mean anything, it must be politically protected. Indeed, for a people to really benefit from nationalism, nationalist policies must be pursued in at least three areas—cultural nationhood, political sovereignty and economic independence. Lacking any of these would either render the nation nonexistent or put it at the mercy of other nations not necessarily concerned with its best interests.

Nationalism’s Three Components and What They Look Like

Let’s take a quick look at the three aspects of healthy nationalism:

Cultural nationhood: the set of policies contributing to the preservation of national culture and national identity and providing for the assimilation of newcomers into the national community.

Political sovereignty: the ability for a people to conduct affairs of governance by its own legitimate means, unmolested by any outside force, be it another nation, overreaching international institutions, or sub-state actors like corporations, criminal syndicates, and secessionist insurgencies.

Economic independence: a nation-state’s ability to conduct its relations with the outside world on its own terms, rather than on terms imposed upon it. This requires the maintenance of a diverse economy, a vibrant population base and sufficient capital-production capabilities based in the homeland.

Multicultural cosmopolitanism, the formation of international institutions, and economic globalization do not necessarily negate these expressions of sovereignty and nationhood and independence—indeed, they can buttress and support them—but taken in excess, the forces of globalization do undermine nationalism and easily lead publics to believe that their cultural, political, and economic sovereignty are at stake; hence the “take our country back” spirit of Western populist movements.

As my friend and mentor Michael Lind wrote a while back, in a magisterial must-read study of the history of liberalism and republicanism, if the Western nations and their elites practiced nationalism properly, the West would:

“…resemble the world order favoured by the so-called ‘sovereigntists’ in Beijing, New Delhi, Brasilia and Moscow more than that favored by contemporary Washington and Brussels….

The globalist liberal goal of a single, rule-governed, borderless global economy would be rejected. There would be an eclectic mix of free trade, managed trade, and protectionism, with developing nations allowed to protect their ‘infant industries’ as did Britain, the US, Germany and Japan when they were rising industrial nations. Immigration would be regulated in different ways by different countries in the interest of their working-class majorities.”

The primary reason such a nationalism is not pursued in the West at the moment, of course, is because the West is ruled by cosmopolitan internationalist elites.

Moving Forward

As suggested earlier, there really is no way to get around the question of national identity and its political consequence, nationalism. Like all things integral to the human condition, it must be accepted and managed, not expunged.

I’m as terrified of Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen as anybody else, and I probably detest them even more than most liberal cosmopolitans do, because they make a mockery of the nationalism I revere, bastardizing it into something contorted, disgusting and unrecognizable. But Western elites won’t be able to manage that populism simply by condemning it and doubling down on internationalist and cosmopolitan policies. At some point they must recognize the concerns of large swathes of the public, and like all good politicians, balance those concerns and interests with those of other groups under their jurisdiction.

All this requires a reorientation of policy in the West towards some form of inclusive nationalism rather than the cosmopolitan globalism epitomized by the present elites and their policies. It’s not forthcoming anytime soon. But hopefully with time, the elites will start to get it.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.