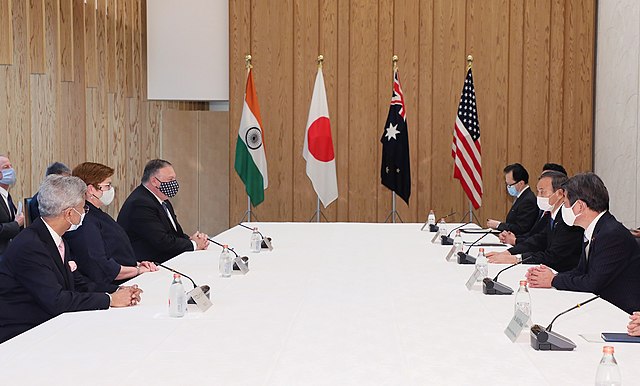

LOS ANGELES — Last month, four of the most important leaders in the Indo-Pacific region met up at the White House. U.S. President Joe Biden welcomed Indian prime minister Narendra Modi, Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga (no longer prime minister) and Australian prime minister Scott Morrison All to the first in-person meeting of the “Quad,” a security forum whose rise seems to directly mirror China’s increasing assertiveness on the international stage.

As some analysts speak of a “new Cold War” beginning between the United States and China, some have begun to compare the Quad to NATO, a military alliance that was founded to counter the rising power of the Soviet Union in Europe. While Quad leaders insist that this new vehicle for dialogue is simply meant to promote general peace and cooperation throughout the Indo-Pacific, the timing suggests that the organization’s newfound prominence is directly correlated with China’s continued rise and increasingly aggressive orientation in foreign policy.

Despite these similarities, however, experts say that comparing the Quad and NATO does not capture the large differences between the two organizations, and that at least for now, the Quad is not a formal military alliance on the model of NATO.

Originating from cooperation between the four countries in the aftermath of the Southeast Asian tsunami disaster, the Quad was first established in 2007.

“The fact that things went so well after, in terms of cooperation, after the tsunami, I guess convinced the four countries that they could work together on other issues of mutual concern,” said Derek Grossman, a senior defense analyst at RAND Corporation and professor in the USC Department of Political Science and International Relations. “Its initial iteration consisted of diplomatic meetings as well as military exercises, and was especially supported by then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who saw it as a vehicle to promote liberal values throughout the Pacific.

Although it initially fell apart due to domestic challenges, as well as pressure from China who disapproved of the organization from its very inception, the Quad was reestablished as part of the Trump administration’s rebranding of the Asia-Pacific theatre as the “Indo-Pacific.” This brought India, the second largest country in the world and a rising superpower, into the fold with countries whom the United States has had long-standing security cooperation and arrangements with. This is notable, as India is one of the founders of the non-aligned movement, and has historically avoided involving itself in defense cooperation.

However, after border clashes with China and China’s long-standing alliance with Pakistan, India has become more assertive. Although the country still rejects common defense arrangements, India is becoming increasingly comfortable with what its leaders have described as being “multi-aligned.”

Other Quad countries have also recently found themselves in more challenging circumstances related to China. Australia, which was able to sustain its economy despite the 2008 financial crisis on trade with China, has become very concerned about Chinese influence in their country and consequently reversed much of their China policy, entering into a trade war with the country that has buoyed their economy for decades.

Japan is extremely concerned about rising Chinese assertiveness in the East China Sea, especially around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Dao Islands. The country is also wary of increased pressure on Taiwan, a strategically important island for Japan’s own security.

The United States under former President Trump identified China as an “adversary” of the country and entered into a trade war. Although president Biden has sought to tone down the rhetoric used by Trump, he has been slow to significantly change U.S. policy, as being tough on China remains one of the few bipartisan issues in Washington.

Yet the Quad is not a military alliance in the way that NATO is. The most important difference between the two is a lack of a collective defense arrangement.

While the US has collective defense treaties with Australia and Japan, none of the other countries are obliged to defend one another. Even when it is apparent that it is meant as a counterweight to rising Chinese power and aggression, the Quad will not name countering China as its uniting purpose, instead citing comparatively vague ideas of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” guided by “democratic values,” and citing issues as disparate as countering climate change and speeding up global vaccine distribution as important goals.

“It’s an informal dialogue,” Grossman said. “It’s not a formalized multilateral.”

While the Quad may signify to China that there is an increasingly united sentiment among democratic Indo-Pacific nations that their actions are viewed as threatening and of concern, it cannot be said that a line in the sand has been drawn in the way that NATO’s establishment was designed to specifically halt any kind of future Soviet aggression. The Quad’s existence functions more as a vague warning than as a direct threat of war.

The Quad is young, and its future is as uncertain as the future of all countries involved and their relationships with China. It may look to include other Indo-Pacific democracies like South Korea and New Zealand in the future, though those countries also have reasons why they would be skeptical, showing the complicated ecosystem of the modern Indo-Pacific. In South Korea’s case, positive relations with China are seen as essential to any kind of future deescalation with North Korea, the top priority of South Korea’s foreign policy. South Korea is also very suspect of entering into any organizations that include Japan, as it has many unresolved issues surrounding Japanese treatment of Korean people back when Korea was a Japanese colony.

New Zealand, a Five Eyes member often grouped with Australia, seems like a prime contender, but has recently come under fire for backing out of Five Eyes condemnations of China, possibly due to extensive economic ties between the two countries. In contrast to the days of the Soviet Union where an Iron Curtain economically divided East and West, today’s globalized world has led to even higher opportunity costs in angering powerful nations, even those with opposing values or those that threaten your own country’s security. These challenges even affect current Quad members. While the United States may be willing to start a trade war with China, and Australia desperately looking to diversify its foreign trade partners, Japan has reservations.

Saori Katada, a professor of international relations at the University of Southern California, said that “Japan has no interest in decoupling from China,” something that might become expected if the Quad were to become more similar to a formal alliance. Other countries in the region, such as Vietnam, might be interested in joining the Quad. However, the forum would then run into the question of what principles the Quad stands for. Vietnam as an authoritarian Communist country, albeit one very concerned about China’s rise, does not fit with the supposed democratic character of the organization.

These questions of what being a member of the Quad entails for both current and prospective members point to the larger challenges present in the Indo-Pacific. Economic ties and government goals complicate the security picture from being simply divided into pro- and anti-China camps. This in turn limits the Quad’s future ability to ever function as a united bloc.

In light of the circumstances, however, the Quad’s looseness may actually be its strength. By not requiring everything of its participants, the Quad may be able to assimilate diverse countries with diverging interests to act collectively to counter perceived Chinese aggression.

According to Grossman, that is “the beauty of it, which is that nobody is obligated to do anything, except have discussions because they want to.” Katada also finds the Quad more “creative” than NATO.

The United States seems invested in the Quad’s future. Even as Biden has worked to reverse much of the Trump administration’s policies, he “has kept the Quad around and has actually bolstered it,” Grossman said. China may not have been directly referenced at the Quad’s White House meeting, and perhaps no formal military ties were established, but there was a clear message that these four nations are concerned about China’s rise in a way that transcends domestic politics.

That message does not look like it will be changing anytime soon. Just don’t expect it to look exactly like the one sent from the democratic world during the Cold War. As Katada says: “This is a new challenge, and a new solution is needed.”