Pro-democracy protests continue to erupt in Belarus after the fraudulent re-election of “Europe’s last dictator,” Alexander Lukashenko, who has remained in power since 1994. Tens of thousands of protestors have taken to the streets of Minsk in the last month to demand Lukashenko’s resignation. His administration has responded by arresting thousands of protestors, using violent police force against citizens, and withdrawing the accreditation of journalists covering the protests.

Now, as the European Union imposes sanctions on Belarusian officials in response to the government’s election fraud and abuse of protestors, President Lukashenko is turning to Moscow for support. And, Putin has already confirmed that he has organized a reserve of law enforcement officers and is ready to intervene in Belarus “if necessary.” The two countries have even launched joint military drills. With the President’s regime weakened by the protests and the European Union’s condemnation, Lukashenko has had no choice but to authorize Russian military intervention, a move that could potentially lead to Belarus’ annexation, though this remains a distant prospect. In any case, it seems like the clock is ticking for Europe’s last dictator.

While the Belarusian public condemns their authoritarian government, public support for authoritarian leaders remains strong in Poland and Hungary. Poland’s Law and Justice Party and Hungary’s Fidesz Party have maintained power since 2015 and 2010, respectively. And, despite their track-records of antidemocratic reforms, national parliament voting intention polls for Poland and Hungary show that both right-wing parties still hold over 45% of voters’ support.

Will Poland and Hungary find themselves in a similar situation as Belarus if they continue down the path of authoritarianism? The two countries’ quasi-authoritarian politics have already resulted in a significant erosion of democratic institutions, but it is unclear whether it will escalate into a full-blown dictatorship as it did in Belarus.

Though the future of democracy in Hungary and Poland remains uncertain, by analyzing the nature of these two countries’ budding authoritarianism, and comparing it to Belarus’ longstanding dictatorship, we can gain some insight into whether these two countries will follow in Belarus’ footsteps.

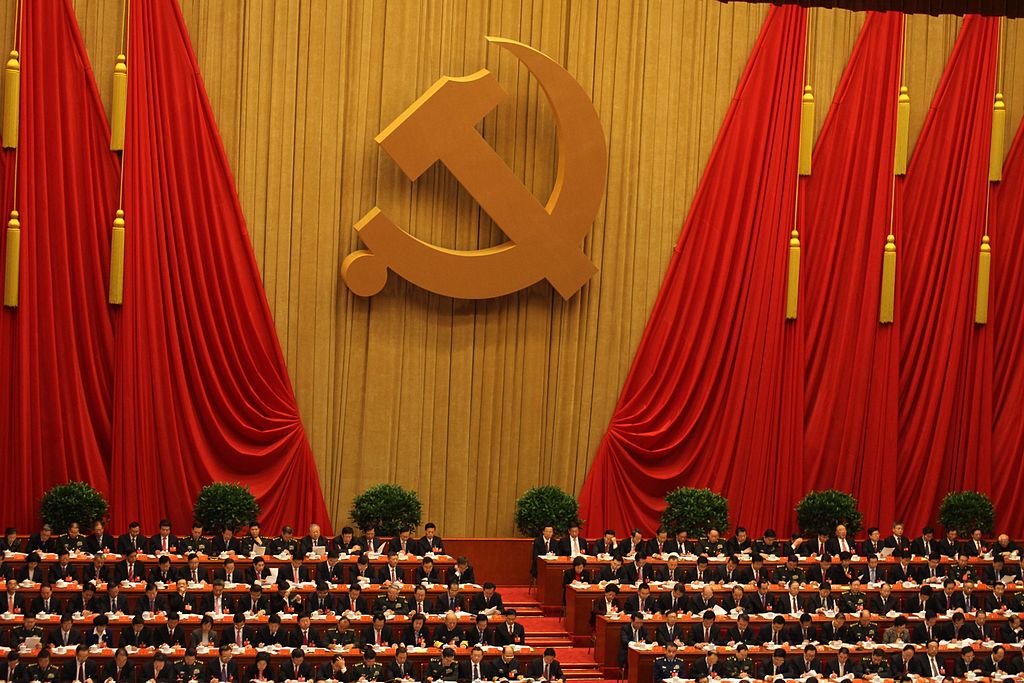

Unlike Poland and Hungary, Belarus was never really a true democracy. Alexander Lukashenko was elected as the first President of Belarus in 1994, immediately after the country gained its independence from the Soviet Union, and has maintained power ever since by manipulating elections, repressing political dissension, and undermining the rule of law. In contrast, Poland and Hungary, transitioned to Western-style liberal democracies after their break from the USSR in 1991 and 1989, respectively. Both countries also joined liberal democratic international institutions, the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Thus, it is clear that Poland and Hungary’s histories differ significantly from that of Belarus.

Yet, Poland and Hungary’s recent political maneuvers mirror Lukashenko’s early authoritarian tactics. Though Lukashenko is now subject to popular disapproval, he was once favored by his people and elected on an incendiary populist platform in 1994. He harnessed this populist support in 1996 when he persuaded voters to approve a new constitution through a referendum. This new constitution gave Lukashenko the right to lengthen his presidential term, rule by decree, and select one third of the upper house parliament representatives. And, in 2004, he completely eliminated term limits through another allegedly rigged referendum. Since then, his administration has consolidated power over all governmental institutions.

Similarly, Poland’s Law and Justice Party and Hungary’s Fidesz Party rose to power through inflammatory right-wing, ethno-nationalist, populist politics. And, though the two parties have relied on democratic elections to maintain power, they also tend to have a general dislike for democratic institutions. Accordingly, Hungary and Poland’s leaders have struck a balance between preserving and dismantling democratic institutions to maintain political power while gradually advancing authoritarianism.

Since 2015, the Law and Justice Party in Poland has used its control over the legislative and executive branches of government to take over the judiciary, effectively dismantling the democratic rule of law. In 2018, the Law and Justice Party founded an “extraordinary appeal” chamber made up of appointed officials that has the power to reverse any civil, criminal, or military court decision made since 1997. This government body also has the final say when it comes to elections, making the prospect of unfair elections all the more likely. And, in February 2020, incumbent President Andrzej Duda adopted legislation that gives politicians the power to fire judges for perceived unfavorable decisions and forbids judges from criticizing the president’s judicial appointments.

Hungary is following a similar path, as the Fidesz Party, headed by Prime Minister Victor Orbán, has continued to attack judicial independence since its return to power in 2010. In fact, just like Belarus’ Lukaneshko, the Fidesz Party adopted a new constitution in 2010 that weakened judicial checks on its power. Similarly to Poland, Hungary created a parallel court system in 2018 controlled by the executive government with the purpose of overseeing elections. Additionally, Orbán has modified electoral laws to ensure he remains in power by redrawing the electoral map and giving ethnic Hungarians outside of the country voting power.

Through judicial and legislative reform, both Hungary and Poland have eroded the democratic rule of law and democratic elections. As in Belarus, by undermining the power of the judiciary, they have eliminated the right to a fair trial and transformed the justice system into a weapon for political harassment and persecution. And, without an independent court system to check the validity of elections, they have also paved the way for electoral fraud.

COVID-19 has only exacerbated the rise of authoritarianism in these two countries, as the Polish and Hungarian governments have used emergency legislation to squash political dissent and give themselves sweeping powers. In Poland, President Andrzej Duda exploited the pandemic crisis to cripple his opponents and secure his re-election in July. While campaigning for re-election, Duda imposed social distancing restrictions for everyone with the exception of himself, giving him an advantage over his opponents who could not effectively campaign. The Law and Justice Party is also taking advantage of social distancing restrictions to advance controversial conservative legislation, such as increased constraints on abortion. In the past, similar legislation has succumbed to the pressure of large-scale public protests. However, under coronavirus restrictions, protesting is no longer an option.

In Hungary, authoritarianism is accelerating even further, as Prime Minister Victor Orbán has virtually declared himself dictator through emergency coronavirus legislation that gives him the power to rule by decree indefinitely. Technically, parliament can still revoke these emergency powers. However, with the legislative branch dominated by Fidesz Party loyalists, this outcome seems highly unlikely. Additionally, the legislation allows the Hungarian government to jail anyone for up to five years if they publish false or agitating information, allowing for greater censorship of political opponents.

Poland and Hungary’s political moves seem to be straight out of Lukashenko’s authoritarian playbook. The two governments have undermined the democratic rule of law, suppressed political dissent, and meddled with fair elections. And, it has not gone unnoticed. Poland and Hungary’s democratic backsliding has already received criticism from the European Union. And, in the case of Hungary, its budding authoritarianism has strengthened its relationship with Russia, representing a potential security risk for NATO.

If indeed this path leads Poland and Hungary down the same road as Belarus, perhaps they should consider sticking to democracy. These two countries’ leaders should view Belarus’ crisis as a cautionary tale about the consequences of authoritarianism, and shift their course now before they find themselves in Lukashenko’s position‒ on Russia’s doorstep.