LOS ANGELES — In May 2020, South Korea experienced a new outbreak of COVID-19 cases in Itaewon, Seoul’s popular nightlife district containing clubs that cater to members of the LGBTQ+ community. Patient zero was a 29-year-old man who visited several bars and clubs one evening. He was identified and the locations he visited were published online through contract tracing efforts from government officials.

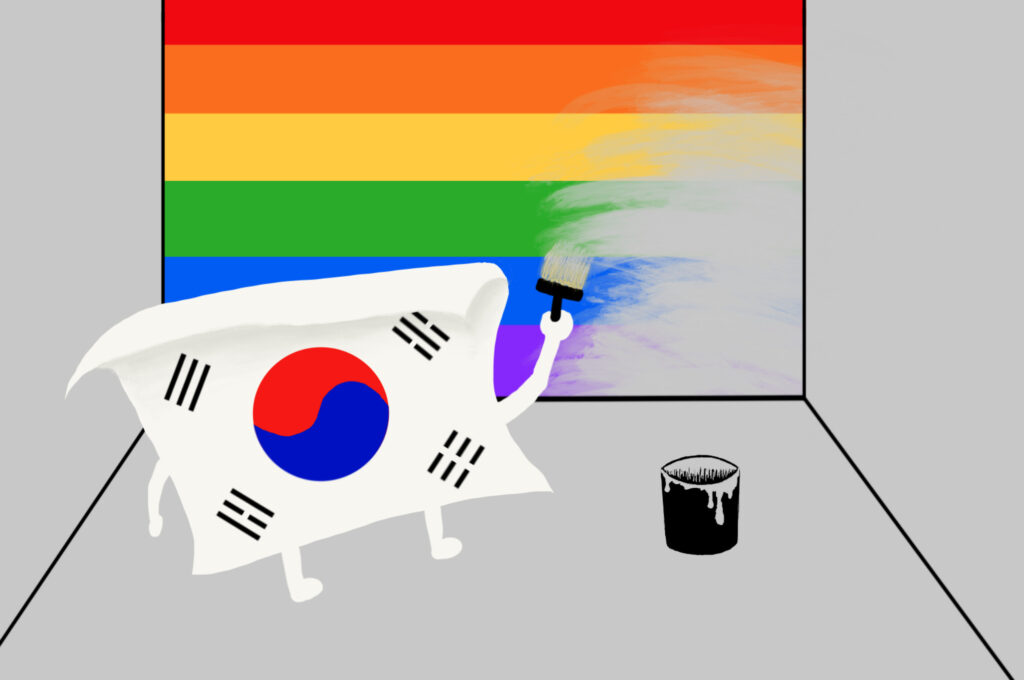

However, this form of intense contact tracing among Itaewon visitors risks exposing their LGBTQ+ identities to the public. Given that South Korea’s legal system provides little protection against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, many of these people may face societal stigma, financial and personal consequences.

South Korea’s extensive contact tracing efforts of the approximately 5,500 people who visited Itaewon during that week began with phone numbers, but moved to location tracking through credit card data, security camera footage and home visits if the provided phone numbers were fake or calls went unanswered. About 3,000 of those phone numbers were useless, prompting visits from Seoul authorities.

The Chicago Council on Global Affairs quoted Itaewon-attendee Lee Youngwu in an interview, where he spoke about the impact of these tracing efforts and subsequent identity exposure.

“My credit card company told me that they passed on my payment information in the district to the authorities,” he said. “I feel so trapped and hunted down. If I get tested, my company will most likely find out I’m gay. I’ll lose my job and face a public humiliation. I feel as if my whole life is about to collapse. I have never felt suicidal before and never thought I would, but I am feeling suicidal now.”

This pattern of the government ignoring and endangering LGTBQ+ people and their concerns is not new in South Korea. Although male and female homosexuality is not illegal, civil unions, marriages and partner benefits are not legally recognized. Further, there is no protection against employment discrimination.

Gay men in the military “engaging in homosexual behavior” may spend up to two years in prison according to the military penal code. South Korea’s military is equally discriminatory against transgender people. In January 2020, staff sergeant and tank driver Byun Hui-su was discharged from the military after undergoing gender reassignment the previous December in Thailand. While her superiors were initially supportive of Byun’s decision, anti-LGBTQ+ protestors called for her immediate dismissal and convinced the army’s review board to follow suit. Byun had been an active military member since March 2017 and appealed unsuccessfully for reinstatement as a female soldier.

In March 2021, Byun was found dead in her home at age 23. Unable to get in contact with Byun since Feb. 28, her worried counselor at Sangdanggu National Mental Health Center called police. The cause was later determined to be suicide.

In October 2021, a landmark verdict came in a South Korean court’s ruling that Byun’s dismissal was unlawful and discriminatory. The army’s previous justification was based on a law that allowed the discharge of soldiers with physical or mental disabilities unrelated to combat or service; Byun’s “loss of male genitals” was considered a disability. Despite this win for the LGBTQ+ community, there has still been no rule change to allow transgender people into the military.

LGBTQ+ couples are also not permitted to adopt children. More recently, in early 2021, Seoul’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family announced its plans to expand the definition of family so that single parents and unwed but cohabiting couples are considered legal families. This new definition explicitly excludes LBGTQ+ couples.

LGBTQ+ youth also face a unique set of challenges within the academic environment. A report by Human Rights Watch and the Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic identifies some of these concerns in a report as “bullying and harassment, a lack of confidential mental health support, exclusion from school curricula, and gender identity discrimination.” These problems are exacerbated by a lack of support from school staff and administration, leading students to fear that they may breach confidentiality or criticize their identities. Teachers receive no mandated training on working with LGBTQ+ students, and any formal education of LGBTQ+ issues is nonexistent.

Furthermore, youth who have used counseling centers and crisis hotlines created specifically for mental health assistance find these services to be unaffirming and at times openly critical of LGBTQ+ identities.

Attempts at passing anti-discrimination legislation have been contentious and unsuccessful, often facing heavy opposition from religious and conservative groups. A 2007 anti-discrimination bill designed to reinforce South Korea’s basic human rights commitment received backlash because of its specification to protect sexual minorities. Co-sponsors of the bill again attempted to pass it in 2010 and 2013 before it was ultimately repealed. A 2014 bi-partisan bill designed to educate government employees on human rights was also repealed after Christian and conservative groups accused it of promoting homosexuality.

Perhaps one of the most controversial pieces of legislation was the Seoul City Charter of Human Rights, pledged by Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon during the 2014 election and designed to help sustain and respect human rights. After a Citizens’ Committee review, 45 of the 50 clauses initially included in the charter were unanimously approved. However, among the five rejected clauses was one that prohibited sexual orientation and sexual identity discrimination. Under the pressure of protests from both Protestant and conservative groups as well as LGBTQ+ advocacy groups, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced that the rest of the charter needed to be passed unanimously. The votes were split, and after further backlash, the charter was officially repealed.

Since the mid-1990s, South Korea has seen the creation of several LGBTQ+ activist groups and organizations. Among them are Chingusai for gay men and Kirikiri for lesbian women, established in 1994 as successors to Chodonghwe, one of the nation’s oldest minority rights organizations. Chingusai’s website claims one hundred offline members and around 5,000 Internet members.

Chingusai has a number of missions, including activism for the rights of non-traditional families, anti-discrimination in the military, HIV and AIDS advocacy and other educational and counseling programs. Kirikiri, which has since been renamed to the Lesbian Counseling Center in South Korea, offered a place for lesbians to connect with each other, provided counseling to deal with social discrimination and protested against biased media reports.

Another growing organization is Dding Dong, an LGBTQ+ Youth Crisis Support Center equipped with a kitchen, sleeping area, shower room, consultation room and an open hall with computers for educational and recreational programs. This center provides a temporary, safe space for LGBTQ+ youth to spend time and rest without being targeted for their sexuality by family or peers, but is only able to remain open for ten hours a day, five days a week due to lack of government funds.

According to the website, the organization’s name has a double meaning. Dding Dong is a “Korean slang used among lesbian teens when they notice each other” and is often abbreviated to just Dding. Dding Dong is also the Korean onomatopoeia for the sound of a doorbell ringing, tied in with their logo of a house to symbolize that Korean LGBTQ youth will always be welcome when they ring the “doorbell.”

The only LGBTQ+ crisis center in Korea, the website says that “DDing Dong will always be with Korean sexual minority teens so that they will not lose pride and confront hate with dignity.”

One of Dding Dong’s coordinators is Park Edhi, a transgender woman living in Seoul. Park, who attended Byun Hui-su’s funeral, says that being transgender in South Korea means having her identity constantly questioned. Her official documents still do not reflect that Park is transgender, which makes basic services like applying for a credit card challenging.

On the issue of establishing and securing equal rights for its LGBTQ+ citizens, South Korea still has significant progress to make. Just recently, the Seoul Administrative Court rejected a gay couple’s lawsuit against a health insurance company for revoking the couple’s spousal benefits. However, human rights groups continue to campaign against discrimination and society’s perspectives on homosexuality are slowly becoming more accepting among the younger generations.

For the benefit of minority groups, the South Korean government should yield less to the demands of conservative and religious groups, and instead reflect the growing will of its people by taking initiative and opportunities like this lawsuit to push towards progressivism.