Gradually phased into implementation in the late 1970’s, China’s one-child policy was largely viewed as a pre-emptive response to an impending Malthusian trap, the shortage of food and resources precipitated by unsustainable population growth. While exceptions were made for ethnic minorities, rural citizens whose first child is a daughter and most recently for parents who are only children themselves, the policy is easily the most draconian family planning strategy of the 20th century.

Families with more than one child are forced to pay exorbitant fines totaling several times a typical year of wages. In many cases, women pregnant with a second child face intense discrimination, abuse and even forced abortions.

To this day, the Communist Party touts the success of this policy in averting some 400 million births. Unfortunately, anticipated curbing of the population has been largely offset by a paradigm shift in longevity. What few people outside of economic and policy circles grasp is that this policy is largely linked to China’s economic growth miracle. China’s economy has benefitted immensely from having a smaller increase in non-productive dependents (children) relative to its population of productive independents (adult workers). Known in economics as a demographic dividend, this phenomenon is associated with economic growth, as decreases in spending on children correspond to increased investment and per capita income.

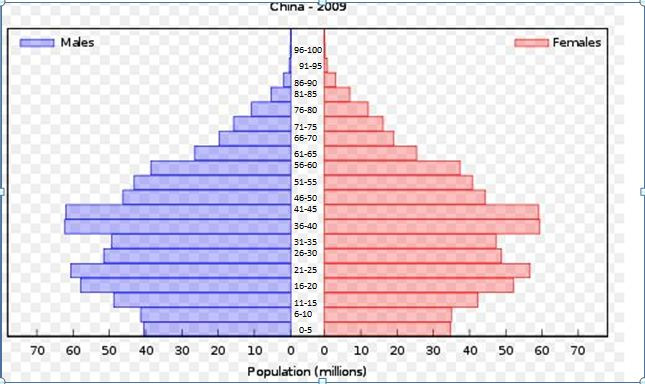

Unfortunately for China, it is about to reach its ‘Lewis Turning Point’, or the point in time in which the large supply of unskilled, agricultural labor migrating from the countryside is exhausted, causing wages to rise. This problem is only exacerbated by the fact that after a three-decade tenure of low birth rates, China’s population is reaching its apex, and about to begin a steady decline.

In an attempt to avoid this population slump and ensuing rise in wages, the Communist Party has initiated reforms to allow for a higher birth rate. To the chagrin of China’s economic policy makers, allowances for families to have additional children have not spurred the birth rate. This is largely because preferences for family size have changed dramatically since the policy’s inception.

In tandem with the increased costs of raising children, many families are reluctant to have more than one child. Thus, in the coming decades, even amidst policy changes, China will find its birth rate stubbornly low. As its surplus of cheap labor dwindles, and wage prices rise, China will quickly lose its hailed place as the world’s manufacturer.

An equally troubling phenomenon is China’s skewed gender distribution. Precipitated by a strong preference for sons over daughters and coupled with China’s proscriptive one-child policy, millions of families have undergone sex-selective abortions to ensure their sole child is male. With some 51 million more males in China than females, China faces numerous social crises. Men who are unmarried, only-children in China (referred to as ‘bare branches’) face numerous psychological issues and disproportionately high rates of suicide. These men have few ties to and little vested interest in the following generation, making them less inclined to be productive members of society and more inclined to engage in criminal activity.

Unequal gender distributions have also precipitated sharp increases in property values across Mainland China, exacerbating China’s growing housing bubble. With millions of bachelors vying for a limited number of unmarried women, owning property has become a prerequisite for finding a wife. This inelastic demand is facilitated by China’s ‘4-2-1’ family structure. Four grandparents and two parents can find themselves providing financial assistance in purchasing real estate for their sole descendent, further intensifying the inelastic demand for Chinese property. As China’s population begins its gradual decline, there will be potential for a burst of the rapidly expanding real estate bubble, as well as a huge contraction in property development.

Another prospect is the increased risk of political instability. Migrant workers and agricultural laborers, who have the most grievances towards Communist Party policies, are the demographic most likely to remain unmarried in China due to their poor employment opportunities. Add sexual frustration to their already poor economic prospects, and there is a strong likelihood that these young men are galvanized into political uprising.

With such tremendous negative impacts associated with China’s one-child policy one can easily liken it to Chairman Mao’s Great Leap Forward (referred to by many scholars as China’s “Great Leap to Famine”). Regardless of what policy changes and amendments to the one-child policy are implemented in the coming decade, there will be some unavoidable economic contractions, social crises and political risks. While many project that China has robust economic prospects in the coming century, the one-child policy’s numerous adverse impacts remain an important consideration in tempering these overly optimistic projections.

The views expressed by these authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.