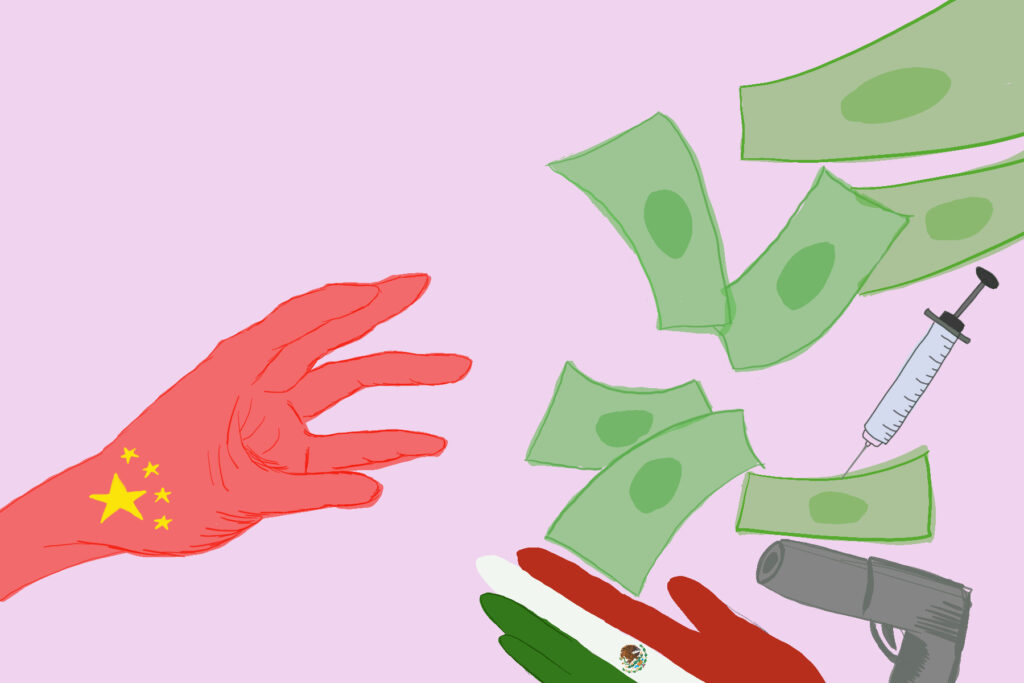

Perhaps nothing is more indicative of China’s rise from a developing country to an economic powerhouse than the sheer number of products sold worldwide that say “Made in China.” From Android phones to Nike shoes to Jalisco New Generation synthetic opioids, China’s manufacturing prowess fulfills the world’s desires like no other nation.

Yes, you read that correctly. Americans want drugs, and China is willing to provide them. As it turns out, China is responsible for the bulk of fentanyl and methamphetamine chemical precursors shipped to Mexican drug cartels. Driven by eager Chinese entrepreneurs and members of the Chinese diaspora in Mexico, China has helped fuel America’s worst drug epidemic in history.

That’s not to mention the issue of money laundering. A Chinese businessman was sentenced to 14 years in prison last year by a federal court in Chicago for conspiring to move $534,206 for Mexican narcotraffickers. However, U.S. authorities estimate that he may have cleaned up to $65 million.

This involvement in crime should be particularly embarrassing for President Xi Jinping. A few years ago, Xi started his “sweep away black” campaign to crack down on organized crime. In response to public panic about crime in China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) initiated a nationwide effort to root out what they call “evil forces” and “black societies.” Yet clearly, these efforts have not contained Chinese connections to the international narcotics trade. One might be tempted to see this as a significant failure of the CCP’s anti-crime agenda.

In reality, Xi Jinping’s “sweep away black” campaign was never about criminal activity in the first place. In fact, according to researchers and China’s state news agency, serious crime rates in China have already been declining for years. When it comes to evaluating the centrality of the CCP in Chinese politics, scholars agree that this campaign was all about ideologically shoring up the CCP’s political dominance and therefore distracting Chinese citizens from China’s economic slowdown.

Sweeping law enforcement operations attempted to build public confidence in China’s understaffed and corrupt police force. Arrests of criminals who gained office in local townships solidified CCP political control at the grassroots level. In a further demonstration of the CCP’s power, local officials expanded the definition of organized crime to include local businesses and used torture to meet conviction quotas. As a result, crimes like bribery that have been tolerated as de facto necessary business practices for decades are now labeled as organized crime. Zhang Wei, a Chinese billionaire, found this out the hard way when a Shenzhen court sentenced him to life in prison last year for bribery. Police claimed he was running an “‘underworld-style’ crime syndicate.”

Critics argue that Xi only cares about solving crime when it benefits him politically, and he has let crime continue if it is economically beneficial. For decades, Chinese authorities have reportedly turned a blind eye toward bribes from Chinese entrepreneurs/companies until this most recent anti-crime campaign. In doing so, authorities strategically helped the Chinese economy’s meteoric rise.

However, when politically advantageous, Xi changed course and began to prosecute allegedly corrupt businessmen. With these prosecutions, local Chinese governments get the bonus of keeping billions in confiscated assets for themselves.

The same principle holds for Chinese involvement in the Mexican drug trade. As long as it is economically beneficial for him not to do so, Xi will not seriously intervene. Trade between China and Mexico surged to over $100 billion in 2021, the highest it has ever been. Investigating claims of drug and wildlife trafficking could jeopardize this economic trade relationship.

Xi has refused to publicly admit that China serves as a source for fentanyl production in Mexico. His token efforts to clamp down on fentanyl shipments in response to American pressure have proven largely ineffective.

Only time will tell if these attitudes towards crime will ultimately backfire for Xi. After abolishing term limits for himself in 2018, Xi has sought to consolidate his power and prove himself as a good leader. The“sweep away black” campaign has been a large part of that effort.

Unfortunately for him, this campaign has significantly eroded Chinese entrepreneurs’ confidence in the law. It has also reduced the legitimacy of his police force, opening the possibility of even more economic trouble and a lack of public trust.

Those are just the consequences within China, however. If China continues to contribute to the synthetic opioid market that causes over 100,000 American drug overdose deaths every year, pressure from American law enforcement and presidential administrations will only increase.

Both Trump and Biden have advocated for a stronger response from Xi, condemning Chinese business’ role in the opioid market. However, until China takes meaningful steps toward curtailing its involvement in the international drug trade, this issue will serve as a point of contention between China and the West for years to come.