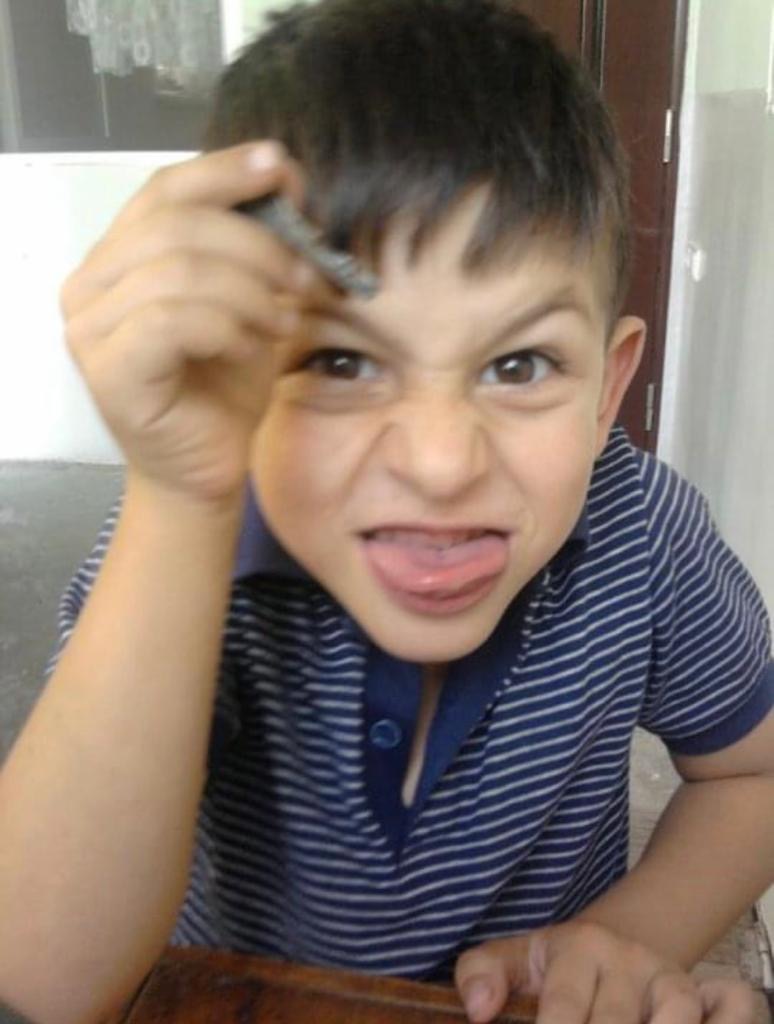

“He was a source of joy for his entire family and neighborhood. You couldn’t just pass by him and not smile. Everyone in the neighborhood felt the same way. When you saw him, you would burst out laughing. That was him — he was the joy of his family. After his passing, there is no joy in his neighborhood or in his family.”

Mher Manucharyan was five years old when Azerbaijan cut the gas supply to Nagorno Karabakh for the second time in 2022. He did not survive.

Today, over 120,000 civilians in Karabakh — including over 30,000 children —- are in danger of facing a similar fate as Azerbaijan’s blockade of the only road connecting Armenia to Karabakh, a lifeline for the local population and its only connection to the outside world, approaches its third week.

On Dec. 13, Azerbaijan cut the gas supply to Nagorno Karabakh (also known by its indigenous Armenian name, Artsakh) for a third time this year. Although the blockade remains, gas supply was restored on Dec. 16 as a result of international pressure, with concerns mounting over the humanitarian implications of a complete lack of gas for households and essential institutions in the winter cold. As schools were closed, daily life in Karabakh was again uprooted, and civilians were left at the mercy of Azerbaijani terror and Russian incompetency, Mher Manucharyan’s story remained fresh in the minds of the few who know it.

Glimpse from the Globe sat down with his cousin, Maria Manucharyan, to record Mher’s story and shed light on the human cost of continued international inaction.

Mher Manucharyan’s Life and Death

“I always saw Mher as the hope of our future, of Artsakh — and before he died, he told me that the hope of Artsakh will never կտրվել [die]. And then he died, hours after he said that.”

Mher Manucharyan was five years old and living in Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh, when Azerbaijan cut the gas supply for the civilian population in March 2022.

His cousin Maria Manucharyan described him as a bright child who was “mature” for his age, having grown up surrounded by the threat of Azerbaijani aggression. She said that after every sentence, Mher would add, “for Armenia.”

“He wanted to become a pilot for Armenia,” Maria told Glimpse from the Globe. “He had to eat, because if he died, then one member of the Armenian population would go down — for Armenia. He had to study well so he could become someone, for Armenia. We had another cousin who was deciding between studying languages and engineering — and he asked, which way do you think you could help Armenia more?”

“He was five years old, but he was so mature,” she added. “I think life matured him.”

Remembering her cousin fondly, Maria spoke of his big hopes and dreams for the future.

“Planes, planes… He loved planes,” she recalled. “He had such a passion for planes that he learned to read when he was four, before school — Armenian, Russian and the Latin script. He learned all of it by himself, with no help, just so that he could read books about planes. You could talk about flowers, and he would somehow manage to describe a plane. His dream was to be a pilot.”

Maria also described him as a gleeful child whose presence made those around him smile. “He would somehow manage to give you joy and energy,” she said. “He never tired, he was always full of energy and he always yelled.”

When Azerbaijan cut the gas supply and refused to allow Russian peacekeepers to make repairs to the pipeline, temperatures hovered above freezing as it snowed outside in Stepanakert and heating became essential. Mher’s parents feared for their young son’s health due to his asthma, which made him more vulnerable to the cold. Mher was not allowed to leave his family’s poorly-insulated house in Stepanakert or go to school, out of fear that he could fall ill amid the gas cut.

“And it wasn’t their house, it was someone else’s, because their house is in Shushi,” Maria added. “You know what happened to Shushi.”

Despite his family’s efforts, Mher fell ill on March 21, initially showing symptoms of a simple cold. Within days, he would be admitted to Artsakh State Hospital in Stepanakert and diagnosed with “pneumonia developed as a secondary bacterial infection because of the cold or the flu.”

“The entire hospital was mobilized around him, but nothing could save him,” said Maria. Despite his doctors’ and nurses’ best efforts, some machines did not work due to the lack of gas and the hospital itself was cold. All his doctors could do was keep Mher warm with their limited resources and make him comfortable in the final moments of his life.

“All I can say is that he didn’t just die, he was murdered by Azerbaijan and they must and will pay for it one day,” his cousin said. “How is it acceptable to just freeze children to death in 2022? How?”

Mher remained his parents’ “last hope” and “the last of everything they had” after they lost his sister two years ago to an Azerbaijani strike during the 2020 Karabakh War. Born in the city of Shushi, a historical Armenian stronghold that was lost to Azerbaijan in 2020, Mher was his parents’ “last of their memory of Shushi.”

“Everybody normalized the fact that it’s just okay, you can kill these people,” his cousin decried. “Whether it’s him or his sister — just because other states don’t recognize Artsakh as one, it’s okay to kill people who live there.”

She spoke of the unimaginable toll Mher’s passing took on his family. “When I talked to them, it’s like they were not alive anymore. Their eyes were empty,” she said. “I don’t know how to describe it.”

“He was their last shred of hope for a future in Artsakh, but he died along with their hope.”

Azerbaijan Blockades Karabakh

“For Azerbaijan, peace means Armenians not existing anymore. What they want is not peace, it’s literal genocide.”

On Dec. 12, a group of Azerbaijanis posing as eco-activists blocked the Lachin corridor, the only overland access point from mainland Armenia to Karabakh after the 2020 Karabakh War (reports soon emerged exposing their government affiliation).

When Karabakh’s gas supply was cut again by Azerbaijan on the second day of the blockade, the need for Mher’s story to resurface became apparent, as a warning for international watchers of the dangers of Azerbaijan’s terror campaign against the peaceful civilian population of Karabakh.

A humanitarian catastrophe is now quickly unfolding as food and medical supplies run out, surgeries are canceled, patients in critical condition — including children and infants — are unable to be transferred to medical centers in Armenia and resources essential to the survival of the civilian population become scarce. Moreover, the daily supply of 400 tons of humanitarian aid to Karabakh from Armenia has been obstructed, and over 1,100 civilians have been separated from their families, unable to return home.

Although Armenia faced a devastating defeat in 2020 following Azerbaijan’s premeditated war against Nagorno Karabakh, a self-declared republic with an ethnically Armenian population that is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, one of the main points of the ceasefire agreement ending the war was that the critical Lachin corridor was maintained, under the protection of Russian peacekeepers.

Russian peacekeepers have thus far failed to uphold their mandate to maintain unobstructed access to the Lachin corridor and protect the local civilian population from Azerbaijan’s attempted ethnic cleansing of Karabakh.

On Dec. 24, a group of Karabakh activists marched to the Russian peacekeepers’ checkpoint near Shushi to demand they put an end to Azerbaijan’s blockade, and a massive rally was organized in Stepanakert the following day calling international attention to the humanitarian catastrophe after the Russians failed to uphold their promise to open the road.

Now, human rights activists and monitors in the region warn of grave humanitarian consequences should the Russian peacekeepers and international community fail to ensure the Azerbaijani-imposed blockade is lifted and the civilian population regains access to its critical lifeline to the outside world. The political implications of Azerbaijan employing human rights violations as a terror tactic against the civilian population, meanwhile, is yet another key facet of this entirely manmade crisis.

Despite local activism, efforts by the Karabakh and Armenian governments and a degree of international outcry, including pressure by UN Security Council members, the blockade has now lasted for almost three weeks. Should Azerbaijan refuse to open the Lachin corridor for a longer period, there is the full potential for a humanitarian crisis of massive proportions.

“In order for Armenians in Artsakh to be considered humans and their deaths to not be normalized, Artsakh needs to be recognized,” Maria Manucharyan said in closing. “It is not just a matter of land, it’s a matter of survival for an entire nation.”