Like everything else in the South Caucasus, discourse around Armenia’s nuclear power plant — labeled “one of the most dangerous” in the world — is entangled in a mosaic of geopolitical complexity and conflicting regional interests.

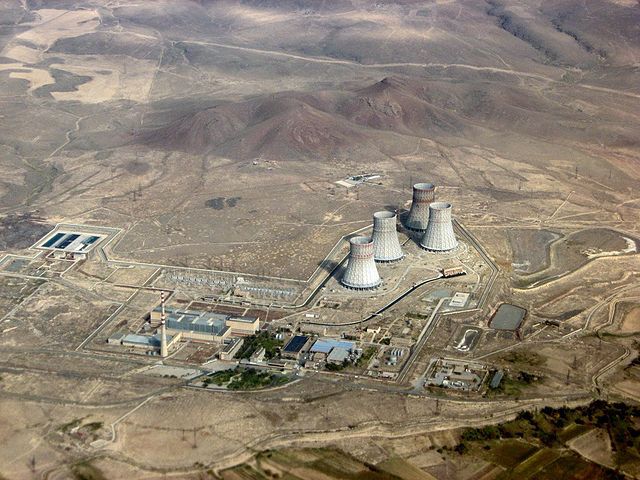

As the only country producing nuclear energy in the Caucasus region, Armenia has relied heavily on nuclear power since 1976. The Metsamor nuclear power plant, located about 35 kilometers from the capital city of Yerevan, generates roughly 40% of the country’s electricity. From its inception as a Soviet-era plant to its current-day operation, the history of the Metsamor power plant is riddled with Russian presence — a presence that tiptoes the fine line of colonization in every chapter it is found.

Today, Russia seems to have taken the long-uncertain future of Armenia’s power plant into its own hands. Currently commissioned until 2026, the life of the Metsamor plant will be extended for another ten years through Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy corporation.

Moreover, in 2021, Russia expressed interest in deepening its energy investments in Armenia’s nuclear power sector and undertaking larger projects, such as the building of a new power unit at Metsamor. Months later, Russia’s interests would materialize into a signed agreement between Rosatom and Armenia’s nuclear power plant.

Notably, although nuclear power is a large component of Armenia’s energy profile, natural gas remains Armenia’s primary energy import, comprising over 80% of total imports. Russia imports roughly 85% of this natural gas to Armenia while Iran imports the rest, the latter partly in exchange for Armenian electricity exports.

With Russia deeply entangled in every nook and cranny of Armenia’s energy sector, an emerging pattern of Russian energy colonization in Armenia — a remnant of a lingering post-Soviet legacy three decades after dissolution — seems to rear its ugly head. The Metsamor nuclear power plant is merely one case study highlighting the root causes of Armenia’s crippling energy dependence on Moscow.

Such a relationship, of course, bears geopolitical implications, as well.

Under the corrupt and criminal leadership of Armenian administrations whose interests aligned more closely with Russia’s than their country’s, Armenia gradually sold its most critical energy infrastructures to Russia. In exchange for securing cheap Russian gas in the short term, the leadership in Yerevan forsook the west’s push for energy diversification.

Fortunately for Yerevan, after the 2018 Velvet Revolution, Armenia is no longer governed by the corrupt oligarchs who sold their country’s energy sector — and therefore a crucial piece of its independence — to Russia; however, the legacy of their corrupt dealings with Gazprom and Moscow at large will remain for several decades to come.

Furthermore, Russia’s investment in Armenia’s nuclear sector comes amid a broader pattern of energy colonization in the region. Similar offers-turned-deals to invest in Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Belarussian nuclear power have been undertaken by Moscow in recent months and years.

Meanwhile, the same recklessness Russian President Vladimir Putin employs in his foreign policy seems to be ever-present in Moscow’s nuclear endeavors, which subject the recipient state — or colony, in the Kremlin’s eyes — to significant safety concerns and associated risks.

In securing Yerevan’s long-term dependence for nuclear energy, Russia significantly also gains another degree of leverage over a former Soviet republic whose geopolitical predicament is a national security risk in its own right. Sandwiched between hostile neighbors Turkey and Azerbaijan, not even the Metsamor power plant has been immune to the dangers this entails.

For its own part, Turkey has repeatedly wielded rhetoric about the dangers of Armenia’s power plant, located roughly 15 kilometers from its border, for political gain. Its concerns, cited far too frequently to be genuine, are also largely hypocritical when considering Ankara’s own partnership with Russia for development of its nuclear sector. Moreover, the Turkish- and Azerbaijani-imposed economic blockade of Armenia, which has financially devastated the country, is a main driver for the necessity of Armenia’s nuclear production.

On the other hand, Baku’s aggressive foreign policy, incessant warmongering and expressed ethnic cleansing agenda against the Armenians located both within its internationally recognized borders and outside pose a unique threat in the context of Armenia’s nuclear power plant.

In July 2021, as tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan were boiling over leading up to Baku’s preemptive war against Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan threatened to employ a missile attack against the Metsamor power plant. Self-evidently, the implications of such an attack would be catastrophic, despicable and constitute a direct terrorist threat to Armenia and its neighboring countries.

Ultimately, Armenia’s Metsamor power plant is not only a symbol of Russia’s energy colonization but a testament to the infinitely complex geopolitical disposition Armenia finds itself in. Like every sector of its host country, competing regional interests and Russian hegemony have overtaken Armenia’s nuclear power plant, as well.

Whether or not the Metsamor plant will weather the storm relies entirely on Yerevan’s long-term planning and the conduct of regional actors.

The current trajectory, however, seems to be Moscow-bound.