When I was two, my dad took me to an Iraq war protest in Dallas.

Proudly dressed in a white kufi with his long beard, a “war kills children” sign hanging from his neck and me sitting on his shoulders, he marched for miles. I don’t remember any of it, of course. But a picture of us has been framed in his house for years.

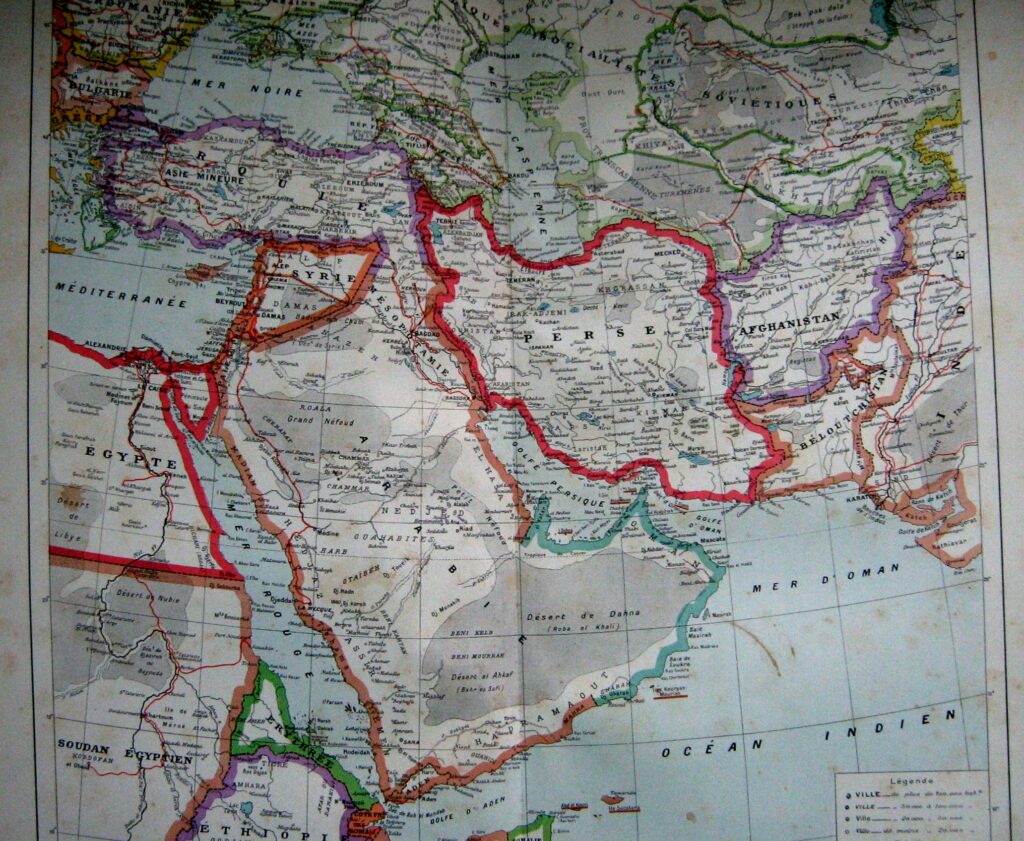

As a post 9/11 baby, I grew up in an era of war. I took my first steps during the height of the invasion of Afghanistan, won my first spelling bee at the start of the Syrian civil war and walked the stage of my 8th grade graduation near the triggering of the Yemen conflict.

The War on Terror effectively brought us to where we are today — desensitized and numb to the reality of conflict. But it’s important to understand the human cost.

At least 929,000 people have been killed by direct violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen and Pakistan. The number of refugees and displaced persons from the United States-led post 9/11 wars are estimated to be around 48-59 million.

To put things in perspective, that’s equivalent to the entire population of South Africa.

Approximately 22% of the world’s refugee population lives in camp settings. Zaatari, as the largest refugee camp in the Middle East and the setting for my sophomore summer, serves as a symbol of the long-running Syrian conflict.

Located approximately 65 kilometers from the Jordanian-Syrian border, in the center of the desolate Syrian desert, the camp has provided shelter and sustenance to over 80,000 individuals in the past 11 years.

Many refugees, most of them women and children, fled from the southern Syrian state of Dara’a to the camp on foot, some with nothing but the clothes on their back and what little they could fit into their pockets.

Deprived of basic needs, adequate access to education and healthcare, and housed in caravans built from scrap metal, they yearn to go back to Syria.

Gassem, an inhabitant of Zaatari since 2013, somehow maintains an embryonic garden of sprouting beans, corn and tomato plants despite abysmal conditions. To him and many others, it serves as a reminder of what they all once had.

“I want to see green again,” said the then-24-year-old, who worked as a vegetable seller in Dara’a. “Green reminds me of home.”

Qassim Lubbad, who also fled from the southern governante in May 2013, has now fathered three children here in the camp.

“When I talk to my children about Syria, and tell them that we have family there, they ask me: What is Syria?”

For the 16,000 children that have been born within the camp’s confines since its inception in 2012, this is the reality. With refugees becoming more familiar with the arid desert surroundings than their own homeland, the memory of Syria in Zaatari is slowly dying.

And along with it, the hope of ever returning.

For Gassem and others like him, over a decade has been lost to the ravages of war. The displacement of over 40 million — and perhaps as many as 59 million over the course of 12 years — raises the question of who bears responsibility for repairing the damage inflicted.

The short answer? We do.

The United States’ military actions and alliances are directly contributing to the very crises humanitarians are trying to resolve. It’s the great American paradox.

“The country, actually bombing cities to rubble and waging wars that kill millions of people, presents itself as a well-intentioned force for good in the world,” explained Nicolas Davies and Medea Benjamin.

From 2001 to 2021, the United States has launched a total of 154,078 bombs and missiles in Iraq and Syria, with a considerable number targeting the same southern governorate that Syrian families like Qassim’s were escaping.

Within the same timeframe, the United States has only resettled 23,364 Syrian refugees, a number that pales in comparison to the magnitude of the crisis. Jordan, despite being a considerably smaller country, has made significant efforts to support the 1.3 million Syrian refugees currently under its care.

The United States’ commitment to humanitarianism is nothing but an empty promise when it fails to employ its resources to assist yet another casualty of its flawed foreign policy.

Our nation is more successful at creating refugees than it is housing them.

For the millions of people residing in regions of ongoing armed conflict due to the United States-led post-9/11 wars, all they can do is flee a hell the United States created and pray for refuge.