In May of 2015, the UAE took another step into the space exploration arena with the establishment of the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) in Dubai. The center, which now operates several observation satellites, is tasked with launching an unmanned space probe to Mars in the year 2020. Dubbed “Hope”, the mission is intended to spark interest in science and technology in the Arab world and represents the UAE’s latest engineering ambitions.

The UAE’s presence in space began in 2000 with the launch of Thuraya-1, the Middle East’s first telecommunications satellite. The satellite’s operator, Emirati cellular provider Thuraya, followed this with the launch of two additional satellites offering cellular services across Europe, Asia and Australia. In 2011 and 2012, AlYahsat, another UAE-based communications company, launched its own satellites for broadcasting, broadband and cellular purposes.

The expansion of Emirati companies into the telecommunications sector represents the UAE’s efforts to diversify its largely energy-driven economy. However, the satellites themselves – which were built and designed by aerospace companies such as Boeing and Astrium (now part of Airbus) – have done little to boost the country’s technological capacity. This is particularly problematic for a country facing a STEM shortage and whose world-famous projects are largely designed by western architects and engineers. As a result, the UAE has established several agencies to foster its nascent space sector, starting with the Emirates Institution for Advanced Science and Technology (EIAST) in 2006, the UAE Space Agency in 2014 and the MBRSC in May of 2015.

So far, these organizations have largely relied on foreign entities to develop their homegrown Earth observation satellites. In a partnership with Satrec, a division of South Korea’s Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), the EIAST launched DubaiSats 1 and 2 to capture high-resolution photographs of the Earth’s surface. But in a country known for its “go big or go home” attitude towards engineering projects (e.g., the world’s tallest building), UAE leaders have pressed for more advanced projects led by entirely Emirati teams.

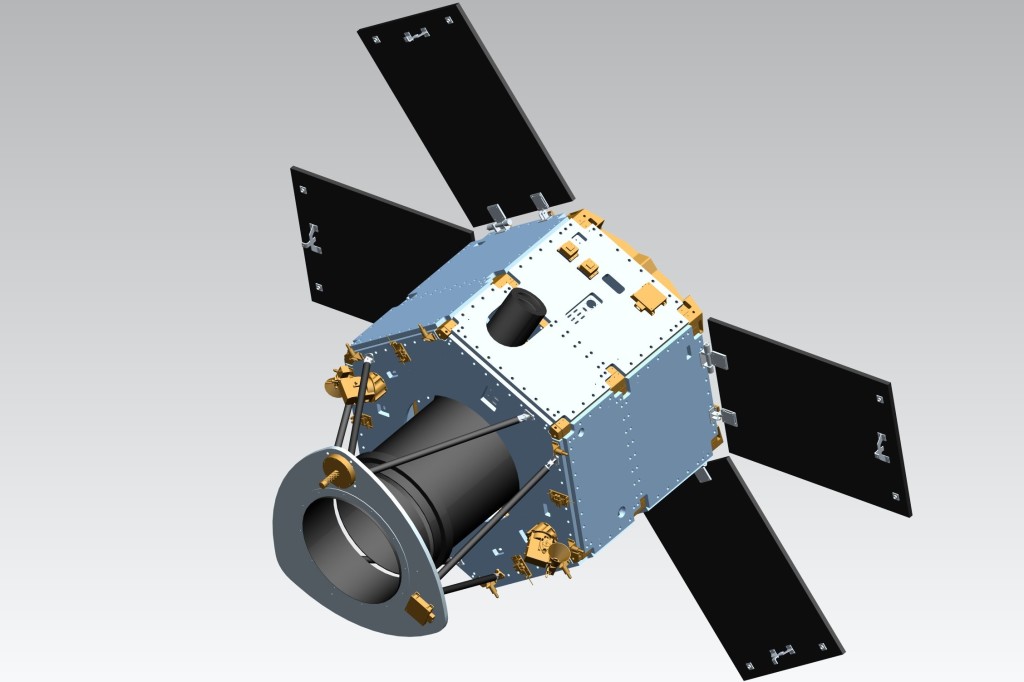

These projects come in the form of an Earth observation satellite known as KhalifaSat and the recently announced Mars Hope mission. The former project will launch on a Japanese Mitsubishi rocket in 2018 and monitor greenhouse gas levels in the Earth’s atmosphere. The Mars mission will collect Martian climate data, and is scheduled to launch in 2020 when the planet makes its closest approach to Earth. In addition to their scientific goals, the Emirati space agency intends for these projects, particularly the Hope mission, to inspire engineers in the Arab world in the same way Kennedy’s Moon speech did half a century ago. To Hope’s project manager Omran Sharaf, this goal is especially important in an era where IS and other terrorist groups seem to dominate the region’s politics. Reaching Mars would send a strong message that the Arab world can develop economically and technologically without violence.

But the transition from low earth orbital satellites to a Martian probe in only several years is an ambitious one and something the UAE can hardly achieve alone. Consequently, the UAE has recently sought additional partnerships with space agencies and universities abroad to further develop their aerospace abilities while maintaining the Hope mission’s 100% Emirati label. Early in December 2015, the UAE Space Agency signed a Memorandum of Understanding with its Russian counterpart, the veteran agency Roscosmos, to pave the way for an exchange of information and training of Emirati engineers. Two weeks later, the UAE struck a similar deal with China, and has collaborated with American universities such as Berkley, Arizona State and the University of Colorado since the project’s inception.

However, US laws such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), designed to protect American space and military secrets, have stymied cooperation between the US and UAE. ITAR restrictions already posed challenges for the UAE’s space program: last year the regulations prevented Airbus from using US-made components to build an observation satellite for the UAE’s armed forces. Since at least March, officials from the UAE have sought to prevent similar restrictions and to take advantage of the US’s experience in space. In November, officials from the two countries formed a committee to iron out ITAR exemptions for the UAE but it remains unclear if concrete progress will be made.

With private companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin pioneering reusable launch vehicles and countries such as India and China attempting their own Mars missions, the space exploration field is evolving quickly. If the UAE wants to make its mark in that sector, it will require sustained motivation and continued cooperation with foreign entities. While its aspirations are ambitious, they are not impossible, and achieving them will be all the more important in showing the war-torn Middle East a path forward.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.