This piece is the first part of Glimpse’s “Contemporary Geopolitics Series”

“Who rules Central and Eastern Europe commands the Heartland. Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island. Who rules the World-Island commands the World.” – Sir Halford Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, 1919.

The Breadth of Eurasia

Imagine if the world from Lisbon to Vladivostok were a singular political unit. All the lands from the North European Plain, to Anatolia and the Levant, to the mountainous Hindu Kush, to the jungles of Southeast Asia, would be within this one state. All the greatest battlefields of hundreds of wars would be pacified under one domain. Imagine if all these places were economically integrated, connected by efficient rail and road systems organized by a central power, and generally at peace with each other despite linguistic and cultural diversity. Imagine looking down from space, seeing the world’s largest landmass, and knowing that it was one.

Such an imaginative vision of Eurasia has been a dream for European and Asian rulers throughout history. For Americans, it is a geopolitical nightmare that must be avoided at all costs. Imagine being the president of the United States and seeing the map of a united Eurasia hanging on your wall in the Oval Office. Eurasia would be the single most frightening thing the US had ever seen—and you would have the responsibility for dealing with it. It would be even more frightening for nations that have traditionally fought wars with continental powers, such as Great Britain and Japan.

Geopolitically, Eurasia is important quite simply because it has the population and resources to match its tremendous size. A state that controls any sizeable chunk of Eurasia has the potential to become a great power, capable of pursuing a hegemonic foreign policy. The USSR controlled the central third of Eurasia, plus the northern fringes of East Asia and a large chunk of Europe from the end of World War II to its collapse. Today, China and the EU dominate the eastern and western thirds of Eurasia, respectively. In the international system, the USSR did carry, a united EU can carry, and China will soon carry political weight comparable to that of the US. It is not difficult to imagine how a unified Eurasia would dwarf all other nations. It is precisely for that reason outside players must prevent its unification.

Historical Geopolitics: The Importance of Eurasia

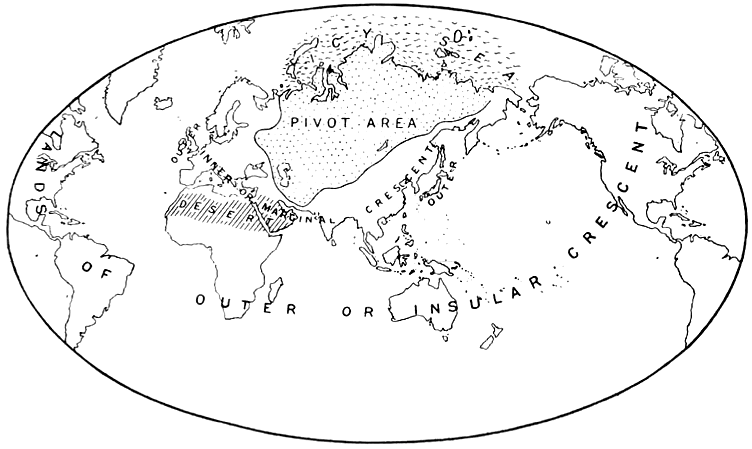

Sir Halford Mackinder was one of the inadvertent founders of geopolitical theory. He famously argued that the key to controlling Eurasia lies in controlling Central and Eastern Europe. It was the key to his “World-Island” and its inner Geographical Pivot of History, or “Pivot Area”. The Northern European Plain provides the historically industrious and imperial nations of Europe with a direct path to what Mackinder called the Heartland. The Heartland is the mountainous yet fertile swath of land in Central Asia, the Caucasus and Russia, where massive quantities of natural resources can be found.[1] Today, Russia and other states such as Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan extract hydrocarbons and minerals from this area for export to industrialized economies in Europe and East Asia. In Mackinder’s time, the pivot area encompassed the Caspian Sea, most of Central Asia and the lands extending northwest across Siberia. It is the central zone of Eurasia that separates larger population centers such as Europe, Persia and East Asia. A single state with political control over Eastern Europe could protect the Pivot Area, access the Heartland’s resources, combine them with the technical expertise and efficient workforces of Europe, and become a superpower with the potential to rule the entire world.

Mackinder realized this in 1904, when he wrote: “The oversetting of the balance of power in favor of the pivot state, resulting in its expansion over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia, would permit the use of vast continental resources for fleet-building, and the empire of the world would then be in sight. This might happen if Germany were to ally herself with Russia.” The German-Russian relationship has revolved around Russia’s ability to supply natural resources and Germany’s ability to efficiently harness their economic potential. Between these two powers lies the critical geography of Eastern Europe. The Russo-German relationship has made the world uneasy for over a century.

Contemporary Eurasian Geopolitics

Geopolitics simply asks: “Where is everyone, and what are they doing?” Everyone once meant nation-states, but in the era of non-state actors such as al-Qaeda and powerful organizations like NATO, “everyone” literally includes everyone, particularly in Eurasia. In our globalized, tight-knit world, anyone with enough weapons, money, or political presence can make a difference. Eurasia has changed drastically since Mackinder’s time. East Asian economies have developed significantly and compete heavily with traditionally well-developed European economies for access to Eurasian resources. Populations have soared in the last century, and new nations have emerged onto the political map. There are more people in the world, and they have become more productive, especially in states like China. These factors are incredibly important geopolitical shifts.

Coupled with the Realist theory of International Relations, geopolitics is an even more powerful tool for observing world affairs. Any student of International Relations can tell you Classical Realism argues that nations pursue power as a means and an end, and Neorealism argues that nations pursue security by accumulating power. Together, geopolitics and Realism ask: “Where is everyone, how powerful are they, and what are they up to?” The answers can be very compelling with regards to foreign policy considerations.

Ukraine is today’s Eurasian geopolitical laboratory. Eastern Europe may well be considered the contemporary pivot area. The Ukrainian crisis is showing us the imperatives of Russia, the discord and noncommittal attitude of the West, and the indifference of the rest of the world. Look at a map: Russia is a wide-open plain. Part of it – Siberia – is a frozen, barely inhabitable arctic wasteland, but the rest of it is accessible for surrounding powers. Ukraine and Belarus cover Russia’s European flank, from which French and German armies have historically invaded. Crimea offers a warm-water port to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, giving it tantalizing access to the Mediterranean and Atlantic. Russia will not tolerate Ukraine being powerfully backed by NATO and the EU; if NATO stretched from the Baltics through Poland to Ukraine, then Moscow would be encircled. The main population core would be squeezed between NATO powers and the frozen tundra of Siberia. Invading Ukraine may have poisoned Russia’s reputation at the UN, but the West cannot afford to react militarily, and the rest of the world really does not care enough about the situation. For Putin, the invasion was a worthwhile preventative security measure. Before long, eastern Ukraine will be forgotten like the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, in which Russia “freed” South Ossetia and Abkhazia (it still bases troops in these former Georgian territories). By creating miniature buffer states in Ukraine and Georgia, Russia punishes its neighbors for “leaning West” while establishing a stronger, Russian-oriented buffer zone in its frontier.

So how can the US and other non-Eurasian powers defend against the emergence of a Eurasian superpower? Thankfully, Earth’s geography is conducive to both the construction of empires and the demolition of them, as Mackinder noted. Eurasia’s human geography is a mosaic of cultures, languages, religions and races that don’t always mix well. More often than not, a small, violent conflict is going on somewhere, if not in multiple locations across Eurasia. Outside powers can exploit Eurasia’s many geographic and cultural divisions to keep a multitude of nations balanced against each other.

Mountains such as the Alps, Carpathians, Caucasus, Urals and Himalayas have directed human movements, settlements and invasions throughout history. Desert areas such as the Gobi and Middle East have drawn inhospitable barriers between radically different civilizations. The Caspian, Black and Mediterranean Seas have facilitated travel and communication in the western half of Eurasia while dividing large ethnic groups from one another. The North European Plain, stretching from France to Siberia, has catalyzed the exchange of cultures, goods, technology and ideas between different nations for centuries. It has also induced bloody wars in every century, by nature of being easily traversable. China’s long rivers and agriculturally productive landscape have made it a traditionally powerful entity, despite being divided and reunited several times in its history. Muskovy and Mongolia, being broad yet isolated, mildly productive plains, have made their peoples eager to expand towards more significant geography to protect their homelands. The mountainous plateaus of Persia and Tibet have cultivated unique cultures. Being secured by mountains on at least one frontier, they have often enjoyed stability despite challenges to development. They have occasionally burst outward in a fit of power or been subdued in times of peril. Central Asia’s mountainous, swirling, varied geography makes it a literal gold mine for outsiders. But alone, Central Asia is deeply divided among clans and tribes who are oft misunderstood, but still overpowered by ambitious foreign actors. Eurasia’s intricate geographic landscape will always provide opportunities for breaking apart nations, for better or worse.

So Alexander tramped from Macedonia to Afghanistan, the Mongols swarmed west towards Europe, and the French marched east towards Moscow. Hitler’s Nazis burst forth across the continent and into Africa, but retreated almost as quickly as they expanded. The Bolsheviks rebuilt and expanded upon the defunct Russian Empire, creating the Soviet Union. Mao turned a turbid, hopeless China into a communist megastate. All of these efforts to unify parts or all of Eurasia have been bloody, tragic and inhumane. The European nations have now embarked on a shaky economic integration project, in the hopes of saving themselves from each other. We can only hope that the rest of Eurasia follows suit, establishing a peaceful future through cooperative diplomacy while remaining divided into states that mirror the physical and human geography of their nations. Yet here we are in the twenty-first century, with active conflicts in the Middle East and on the Russian-Ukrainian border, simmering conflicts in the Balkans, the Caucasus and Korea, separatist movements in Western Europe, maritime clashes in the Pacific and an overall sense of discord among nations.

In Eurasia, the forecast is cloudy with a chance of war.

[1] Mackinder, Sir Halford J. Democratic Ideals and Reality, 1919.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.