In mid-December 2014, Egypt’s military administration passed a new sweeping law institutionalizing a crackdown on civil society. This law forbids “compromising national unity” or “harming national interest,” i.e. engaging in the criticism of government and advocacy for social justice that is imperative for a country in the wake of a democratic transition. The new law also targets organizations that receive foreign funding, echoing the controversial 2013 Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) case, which resulted in jail sentences for 43 individuals, including Americans, who operated foreign-funded NGOs.

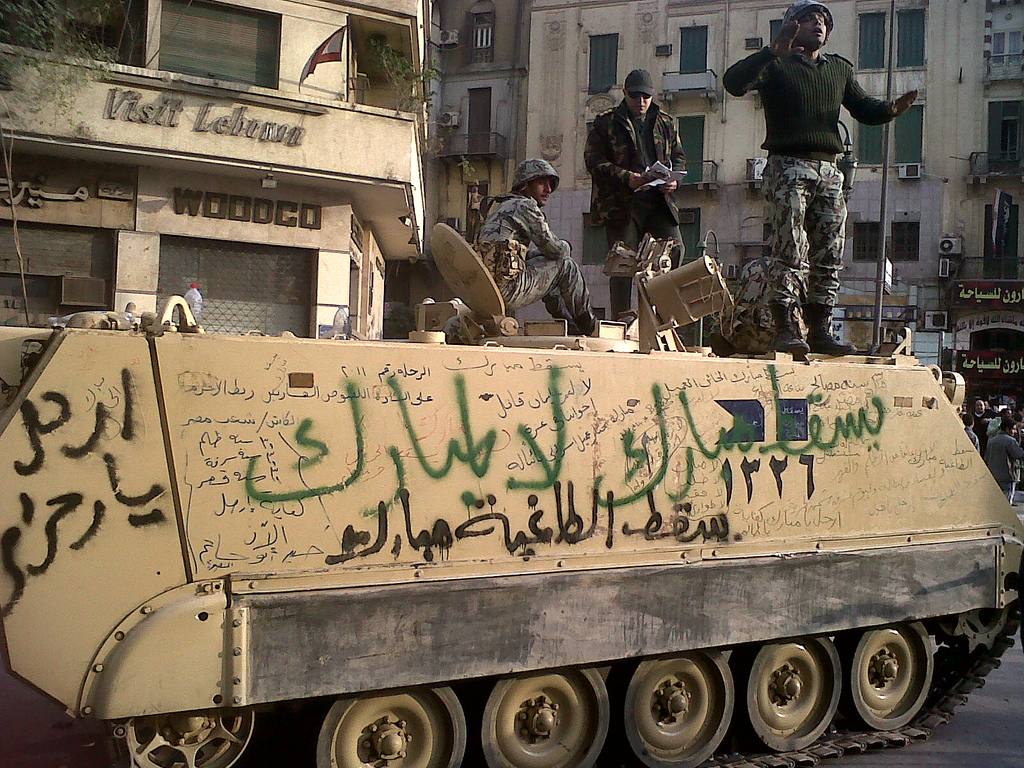

During Egypt’s 2011 popular uprising, calls for reform and democratic justice exploded, and hope for regime change emerged. However, the years since this uprising have brought division and disappointment for former revolutionaries. Unemployment, economic stagnation and political disillusionment have festered in the wake of a corrupt Muslim Brotherhood administration and a subsequent military coup. The struggle between the Muslim Brotherhood and the military today echoes the history of these two groups that have historically battled for power in Egypt. In this latest standoff, the biggest losers have been activists and other civil society groups.

This new anti-civil society law represents the most recent episode in a series of democratic setbacks since the revolution. The 2013 court decision and most recent civil society law are based off a Mubarak-era ruling, NGO Law 84 of 2002, which has been used by both the Morsi and Sisi administrations to justify suppressing popular dissent. This law, which was amended in 2013 to include even more oppressive measures, requires the registration of all NGOs with the government, forbids fundraising and advocacy projects, and can even stop any action of an NGO working in Egypt. This was a shock to international pundits watching Egypt; yet, the most recent version passed in December adds even more restrictions to civil society groups and carries the threat of a life sentence in jail for any individual operating in an NGO seen to violate these regulations.

The enforcement of this law is likely to fall primarily on human rights organizations. Because ensuring human rights are the responsibility of the government, these groups cannot engage in their necessary fundraising and outreach activities out of fear of prosecution. The purpose of these measures, according to the Egyptian authorities, is to prevent “terrorism” by keeping a control on the activities of domestic non-state actors. This logic, while certainly not unique to the Sisi regime, is laughable, since the government is cementing its own legitimacy issues by silencing the dissenting voices of its people.

Does this crackdown mean that Egypt’s revolution is dead? Hardly. This new move by Sisi has generated fierce opposition from both domestic and international actors. Egyptian human rights advocates have drawn parallels between the current Sisi administration and the fascist regimes of the 20th century. The many regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles imposed on civil society will be a formidable setback; however, Egypt’s civil society sector is the most vibrant in the region. The dialogue and ambition unleashed by the 2011 protests cannot be restrained by an oppressive government.

However, civil society will likely undergo a period of stagnation. Under the existing legislation, international organizations such as Freedom House and Human Rights Watch have faced restrictions on their operations, and the most effective domestic human rights organizations are in a state of limbo, awaiting governmental approbation of their official status. Foreign funded NGOs will find their operations compromised with the restrictions on finances and international support.

This new law is a clear indication that the Sisi government is concerned with maintaining a strong grip on its control over Egyptian politics and society, and that civil society will be a new battleground in the struggle over Egypt’s future. Egypt’s position as a regional political and diplomatic leader makes a successful democratic transition and return to stability paramount. However, the aftermath of the revolution has been a protracted partisan struggle for control without real institutional or structural change, undermining the efforts of those who protested and died in Tahrir Square. This does not signal the death of Egyptian democracy, yet is a severe loss for democracy and human rights advocates in the country, as well as the general public who benefits from this work. NGOs such as the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights were central to keeping pressure on Egypt’s transitional government to guarantee free and fair elections and a moderately democratic process. If these organizations are not allowed to continue the fight for freedom, human rights and democracy, this revolution will be lost.