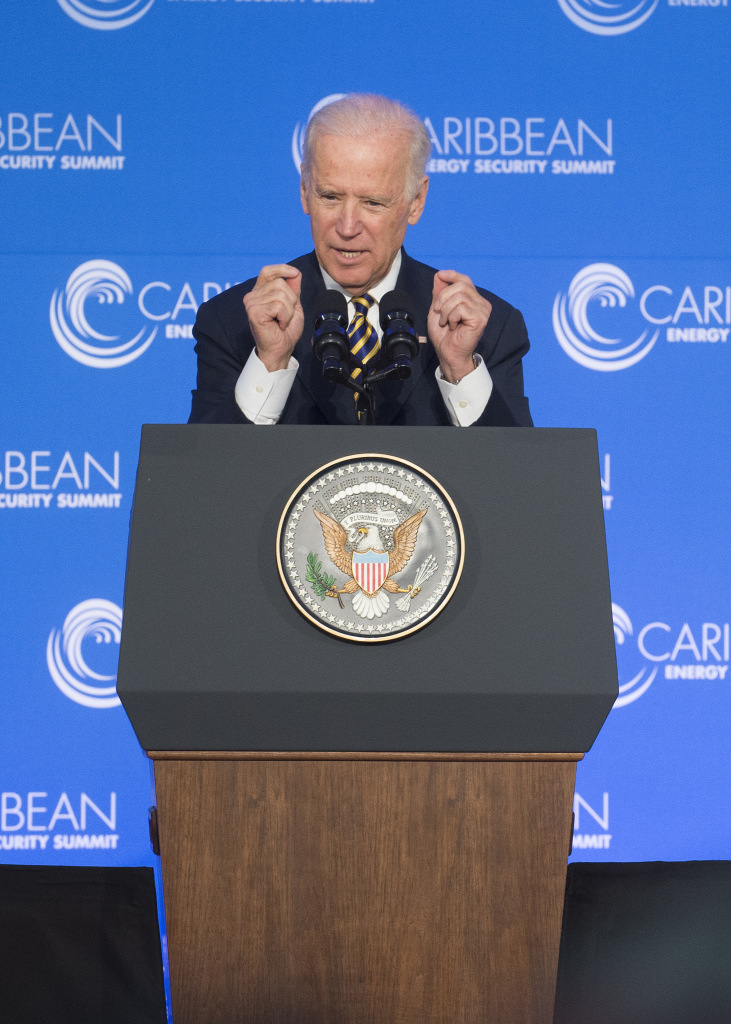

On January 26, Vice President Joe Biden headed the first Caribbean Energy Security Summit, a conference attended by representatives from European, Latin American and Caribbean states, as well as a significant collection of non-state financial actors including the World Bank. Billed as a noble gesture in favor of sustainability and clean energy, the impetus behind the Summit and its intended outcome has more to do with politics and fossil fuels than green activists and solar panels.

The Summit came as the latest stage of the Caribbean Energy Security Initiative (CESI), announced by Biden in June 2014. According to the State Department’s description, the initiative aims to rally governmental, financial and private sector actors across the Caribbean and the world to “promote a cleaner and more sustainable energy future in the Caribbean through improved energy governance, energy diversification, greater access to finance, and donor coordination.” Originally a minor project, CESI has recently taken on an increased relevance on the White House’s agenda in light of collapsed oil prices, leading to the January Summit.

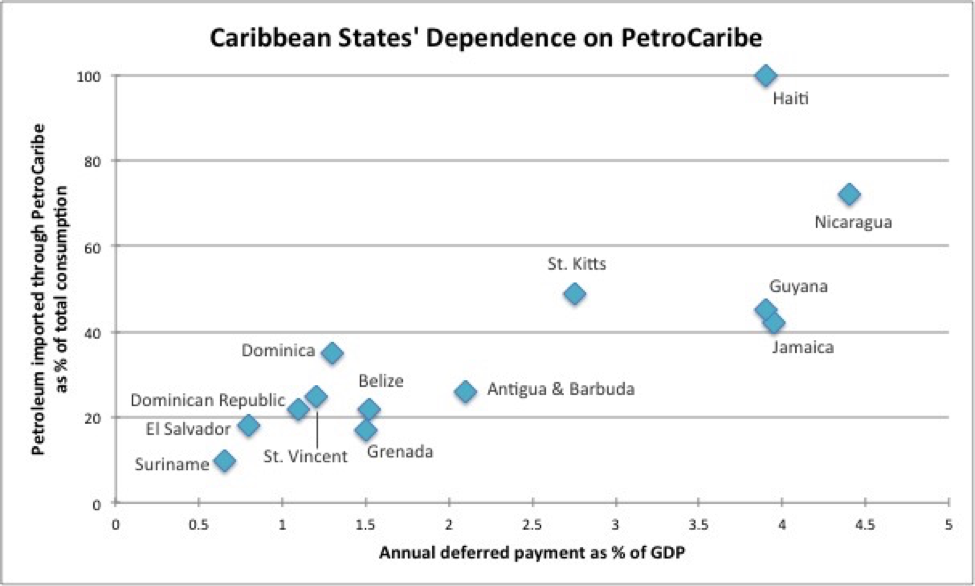

The Caribbean islands have historically been heavily dependent on petroleum imports. Since 2005, Venezuela’s PetroCaribe program has been providing oil to 10 members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), as well as the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and El Salvador, at an average annual loss of $2.3 billion for the state itself: when the market price of oil rises, Venezuela loans a large portion of the cost of exports to the purchasing states on extremely lenient terms. Despite generous loans, many Caribbean countries struggle to finance PetroCaribe imports; with energy prices at home already exorbitant, even artificially low oil prices strain budgets. Needless to say, most Caribbean states could not afford to pay market price to import oil.

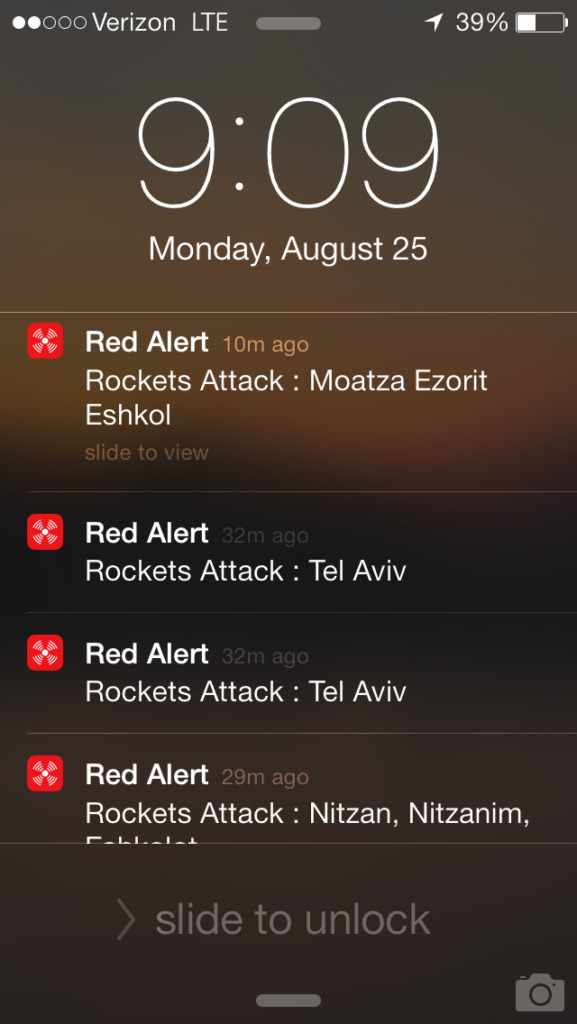

President Maduro of Venezuela initially valued the influence and leverage in the Caribbean that the PetroCaribe program provided, in spite of the monetary losses. But the country’s strained economy is shifting Venezuela’s priorities. Signs portending more stringent terms for PetroCaribe contracts appear as oil prices drop and Venezuela fears it may run out of cash. If the government suddenly stops financing PetroCaribe, under current terms, importing states would only have 30 days before being forced to pay market rates. Hard-pressed financially and thus unable to risk this option, Guatemala withdrew from the program in 2013.

The US has sought to intervene in this volatile situation. If Venezuela were to relinquish its role as the region’s chief energy provider, a space would then open for a new power to take its place—a space the US seeks to fill. Without waiting for PetroCaribe to crumble, the US government has been pushing initiatives in the region: first CESI, then the Caribbean Energy Security Summit.

Meanwhile, Venezuela proves hostile to US involvement in its sphere, spun as aggressive and predatory by headlines like “US Pushes Energy Exports to Undermine Venezuela” The article, published by oilprice.com, concludes, “ultimately the US is seeking to carve out a greater geopolitical and economic influence at the expense of Venezuela,” echoing a popular interpretation of the aim of the Summit. In response, Maduro was quoted by Fox News Latino claiming, “The imperial power of the North [the US]has entered a dangerous phase of desperation, and they have gone on to speak to governments of the hemisphere to announce the overthrow of my government,” personally accusing Biden of carrying out this “coup”.

But if Biden is concerned about straining already frayed relations with Venezuela, he masked his concerns while pitching his view of the future of the Caribbean. Biden’s remarks at the Summit expressed an aggressive interest in Caribbean and Central American energy and security: “This is extremely important to us. It’s overwhelmingly in the interests of the United States of America that we get it right, and that this relationship changes for the better across the board.”

The material reasons behind his eagerness came later in his speech. Biden presented US Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) as a solution to energy insecurity, albeit temporary: “There’s also LNG exporters in the United States with licenses to export to any of your countries, whether you have a free trade agreement or not. If you want gas, go talk to them.” An energy-scarce Caribbean would provide the perfect, geographically close export destination for the US’s fossil fuel boom, increasing demand and perhaps relieving the strain of falling prices. Incidentally, the push resonates with the long-standing goals of David Goldwyn, a former State Department official who pushed Congress to liberalize oil and gas exports and planned the Summit.

Biden’s enthusiasm for LNG was not ignored; the official Caribbean Energy Security Summit Joint Statement mentioned what would presumably be US-provided natural gas. Released on January 26 the statement was signed by states large and small of the Caribbean, Latin America and Europe, as well as notable non-state actors such as the Caribbean Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank Group, International Renewable Energy Agency and the World Bank Group. This wide range of political and financial actors demonstrates the initiative’s impressive multilateral backing.

Though the six operative clauses focus on implementing clean, renewable energy, tucked into the fourth clause is the recognition that “alternative fuels, such as natural gas, can play a useful bridging role.” The small weight given “alternative” fuels – referring actually to conventional fossil fuels – will likely turn out to be misleading. Despite the lip service Biden paid to a sustainable energy transition, the immediate US aims of the Summit are LNG exports and carving out a sphere of influence in the Caribbean.

Beyond these goals, however, Biden aptly proclaimed, “Ladies and gentlemen, when it comes to energy, we’re living in a new moment—not just in the Caribbean, but worldwide.” Whichever direction this new development takes, the US is striving to ensure that it will have a key role in shaping the Caribbean.

The views expressed by this author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.