Syria, Iraq and Ukraine have been reduced to shambles. You’ve seen it all over the news: terrorist turned caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and his Islamic State watch as their influence and power spreads like wildfire across the Levant, while pro-Russian opposition groups wreck havoc throughout the Ukraine, shaking the establishment of the Iraqi and Ukrainian governments at their cores. Millions of refugees and internally displaced persons across the regions suffer from inadequate resources and fear they may never return home again amidst oppositional invasions and airstrikes in cities like Mosul and Snizhne. Thousands of miles away from the comfort of our living rooms we wonder how these states descended into chaos so rapidly in the past few years and why attempts at reigning in their power prove ineffectual at best.

Yet, the leadership in two of these regions has emerged from the entropy unscathed, and, by some accounts, more powerful than ever despite the chaos unfolding within their borders. Bashar al-Assad began his third presidential term last week despite condemnation of Syria’s elections by the European Union, the United States and UN General Secretary Ban Ki-Moon as unfair and illegitimate. According to a recent Gallup poll, Vladimir Putin has enjoyed an 29% increase in his national approval rating this past year, no doubt in response to Russia’s invasion of Crimea and destabilizing role in Eastern Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Syrian political groups remain mired in intense intra-group conflict over how to handle their current domestic situation. With the current split system between Bashar’s Damascus and the opposition-led Aleppo government, little hope remains for any semblance of legitimate rule.

In Iraq, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has been blacklisted and blamed by leaders in the Gulf States and Iraq’s own general public for failing to quash the rebel fighters edging their way towards Baghdad. Mired in gridlock as Parliament members attempt to form a new government, the hope for order and stability in Iraq seems fleeting for the near future.

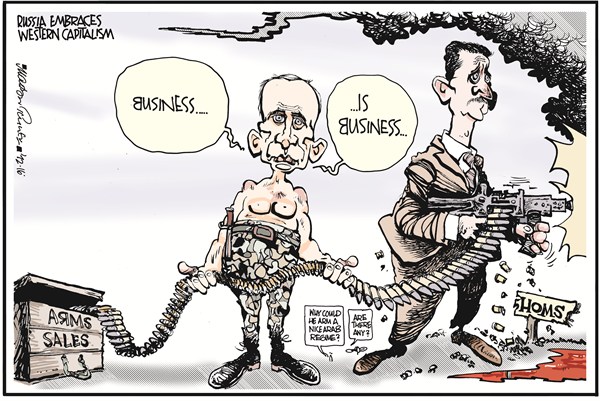

How do Putin and Assad continue to reign with such unchecked power given the fierce opposition by their own citizens –as seen in the Pussy Riot protests and by free speech advocates being arrested for “violating public order”–and, by and large, the Western world? Without question, Russia’s star has risen astronomically in the global political arena over the past year. Damascus, thanks to the generosity of Putin’s government, has greatly increased its military power with Russian-made jets used to hunt down oppositional militias. Al-Baghdadi and his troops have captured the Al-Omar gas field in central Syria, increasing their economic power and threatening the very core of the Iraqi energy sector. Though by no means exclusively, ‘iron fist’politics, tangible gains in national interest and popularly supported cronyism are the three driving factors in the success of Bashar, al-Baghdadi and Putin.

Dominant leadership has proved crucial to the success of Putin’s Russia. Since 2000, his charismatic authoritarianism has pushed the country to the forefront of the political arena. By setting a precedent of swift, no-holds-barred action against opposition groups during the Second Chechen War, Putin enjoys popular support as a leader who demonstrates potency and has a clear vision for the future. Bashar too continues to hold absolute rule despite the scattered battlefields across the country, authoritatively quashing rebel groups with brutal barrel bombs and leaving millions displaced or in flight from their homeland. Al-Baghdadi’s Islamic State has also risen as an effectual political and military model that wins citizens’support thanks to welfare services and public works projects, despite grave ideological differences within the group’s vision of a caliphate and fundamentalist fueled sharia law.

All three leaders also boast a clear grand strategy for what they perceive as the public’s interest. Putin’s vision of Russian exceptionalism, reiterated in his speeches to the people, now inspire a new wave of popular support throughout the country, and his actions in Crimea and the rest of Ukraine reflect a prototypically powerful Russia rising from the ashes of the USSR’s breakup in 1992. Pro-Russian rebel forces now control the majority of Eastern Ukraine –including the area where Malaysian Airlines MH-17 was allegedly shot down by opposition forces with Russian-supplied surface-to-air missiles–further illustrating their influence. In Bashar’s inaugural speech last week, he called for a greater focus on caring for the people of Syria, decrying attempts from the West to uproot existing order in the country and promising to protect the Syrian people against further bloodshed. While his declarations of victory of terrorism don’t ring true for Syrians in Aleppo still recovering from last week’s airstrike, his military and political capabilities will undoubtedly keep Syria safe from international threats and slowly but surely defeat the Free Syrian Army from within its borders. Al-Baghdadi’s comprehensive public works campaigns and acquisitions of oil and gas fields in both Syria and Iraq have won the support of citizens and business leaders alike who hope to cash in on the loot.

Yet, the widespread, intricate cronyism that ties the three together is the most damning evidence of all. Reports recently surfaced that the Islamic State may be selling Syria oil and gas through secret back channels, even though the Syrian government vowed to “eliminate” the extremist Sunni terrorist organization, which it considers a threat to Bashar’s presidency. Russia too has joined in on the action, providing the Syrian regime with weapons and jets to combat their civil war, seeing value in defending a vital economic and political ally in the Middle East.

Sustained growth by these three powers gravely threatens American political and economic interests; yet, the US has proposed ineffectual sanctions that, while crippling to Syria and Russia’s economy, have done little to nothing to ease tensions and render solutions. Putin hasn’t batted an eyelid: the creation of the $100 billion BRICS Development Bank poses a serious threat to both the US dollar and the influence of Western-based lending institutions like the World Bank and IMF. While a three-front war in the regions would be strategically challenging and politically impossible, more direct action must be taken in Iraq, Syria and Russia. While America’s presence in Iraq is growing, its purely advisory role lacks the necessary punch to rid Iraq of ISIS.

While war hawks and some leaders in the US want to sustain the country’s role as the international police force for conflict and corruption around the world, it is clear that a majority of Americans want to focus on domestic economic and political rehabilitation. Ultimately, the country may no longer be able to foot the bill, either economically or politically.

The views expressed by these authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.