This article is the first part of Glimpse’s series on Iraq

I heard a joke once. The joke was that Winston Churchill, who in 1921 was serving as Secretary of State of the British colonies, had created the British protectorate Transjordan (now the country of Jordan) by drawing an arbitrary line through Saudi Arabia. The odd zig-zag shape the border creates is supposedly the result of Churchill’s hiccups following a particularly drunken lunch.

Some joke, when thousands of people are displaced because of a hiccup. But whether or not Churchill told this story in jest, and whether or not he really had one too many the day he created the border between what is now Jordan and Saudi Arabia, the fact remains that it is no joke, and no secret, that the borders of the Middle East were artificially created by the French and British almost one hundred years ago. Today, the world watches in disbelief as many of the Middle Eastern countries repeatedly collapse into instability.

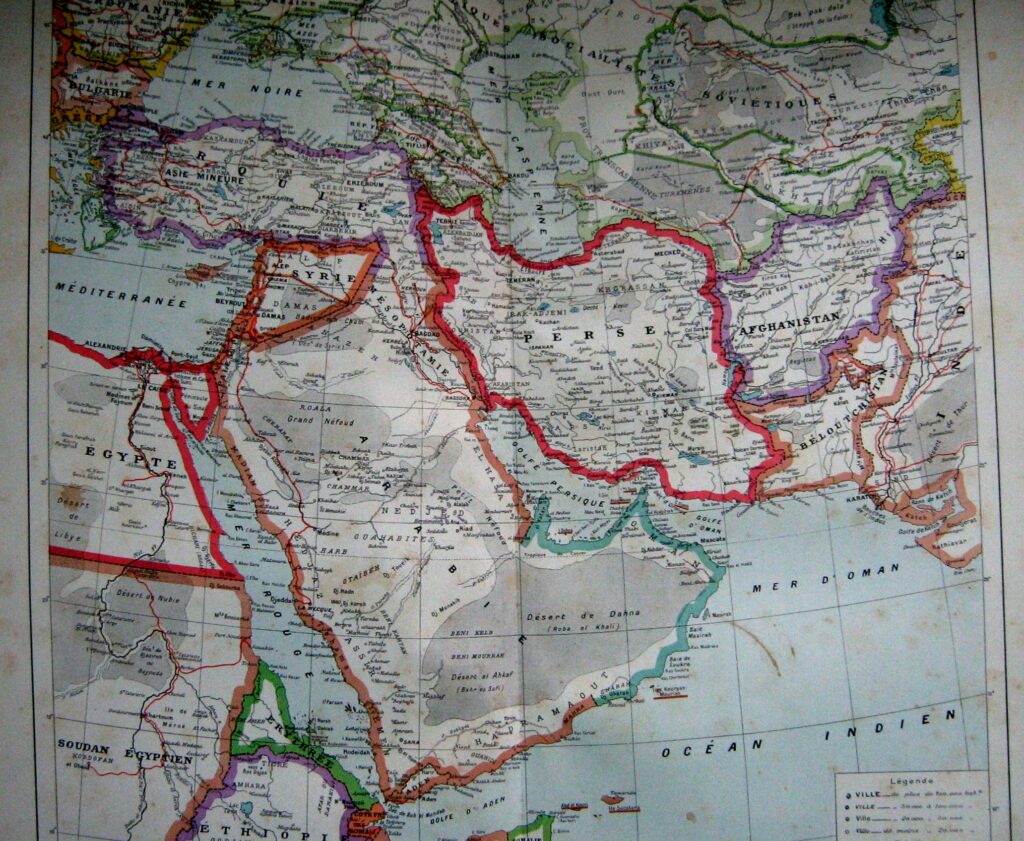

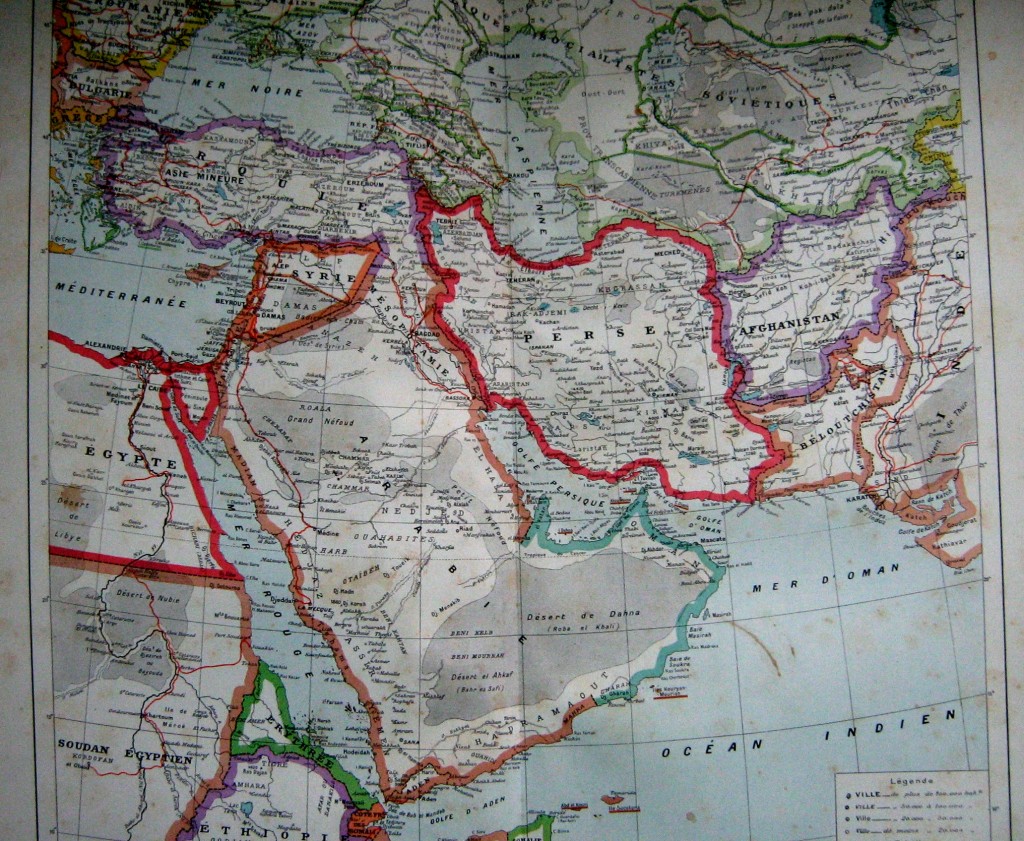

It’s important to study the history of this instability before proposing solutions. In 1915, the Ottoman Empire had been watching its power decline in the face of European global domination for almost two hundred years. Its final, fatal mistake was joining World War I on the side of Germany. As the war continued, it became clear that the Ottoman Empire was not going to survive. Britain and France, the two imperial powerhouses at the time, signed a secret pact called the Sykes-Picot Agreement, splitting the Ottoman territories of the Middle East based on their strategic interests. The agreement drew the borders of (roughly) modern day Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Israel/Palestine and Egypt. It placed each state under the control of either French or British mandate, allowing the two powers to rule those territories “until each mandated state was judged fit to govern itself.”

The system that the Sykes-Picot Agreement forged in the Middle East was not to last long. All of the states created under the agreement eventually did gain independence from their mandate powers. And all of these states have experienced at least occasional, if not continuous, instability and strife in the last one hundred years since the mandate system split them apart.

Above all, instability created by the Arab Spring in 2011 was a wake up call. Not only for the authoritarian regimes that had dominated the governments of the Middle Eastern states since “independence” who were overthrown, but also for the millions of people in the Middle East who had been living under severe repressive conditions for decades. The entire world, too, was shocked by the spread and success of the Arab Spring; few times in history have we observed the stability of an entire region completely fall apart at the same time.

It should have been clear then that if that many people were demanding and fighting for change, something was wrong with the physical nature of the Middle East and its role in global society – the Arab Spring was but a delayed reaction to the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The countries that make up the region had been forced into the Westphalian system – where nation states, not ethnicities or religions, are the dividers of people – by imperialistic powers that cared only for geostrategic and economic dominance. The ethnicities, religions and politics of the people of the region had absolutely nothing to do with the borders that separated them. Could this be why the Middle East has been condemned to conflict? Has democracy never seemed to work in these countries because they cannot be governed by people who never intended to interact with each other?

This question was not voiced during the Arab Spring. The question of borders has only recently been provoked by the near-collapse of the Iraqi state under the Sunni militant group ISIS (The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), which aims to create its own Islamic state under Sharia (strict Islamic law). At the time of this writing, ISIS has invaded and taken control of southwestern Syria and major northern Iraqi cities, officially declaring a caliphate – an Islamic state – in the region. Within the border of what was only a month ago the state of Iraq, there remains a makeshift Kurdish state in the northeast and the significantly weakened Shia majority government in Baghdad.

Many of the questions posed in the last few weeks by the media and global governments are centered on how to stop ISIS from destroying Iraqi and Syrian “sovereignty” – basically, the governmental “right” to control the land defined by the current, Westphalian borders. The insinuation is that ISIS does not have the right to claim the territory that it has taken over. Based on the history of the region and how it was created, though, it has been debated whether the rest of the world has a right to decide this question.

It is not disputed that ISIS has already been the cause of countless human rights violations. But, so have the Middle Eastern authoritarian regimes that found that the only way to tie together their disparate groups of citizens was to strap them together with oppression and violence. Perhaps what the Middle Eastern states need in order to finally end a century of instability is to be allowed to split by natural borders – by borders drawn based on ethnicities, religions and political groups – not by those borders created by arbitrary, imperial hiccups.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.