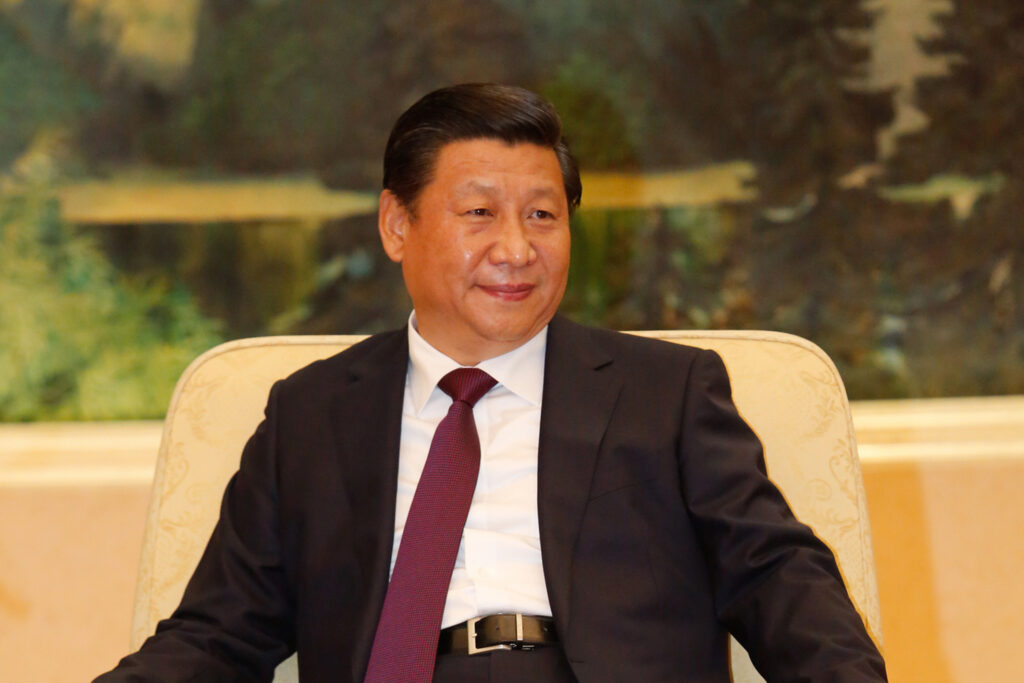

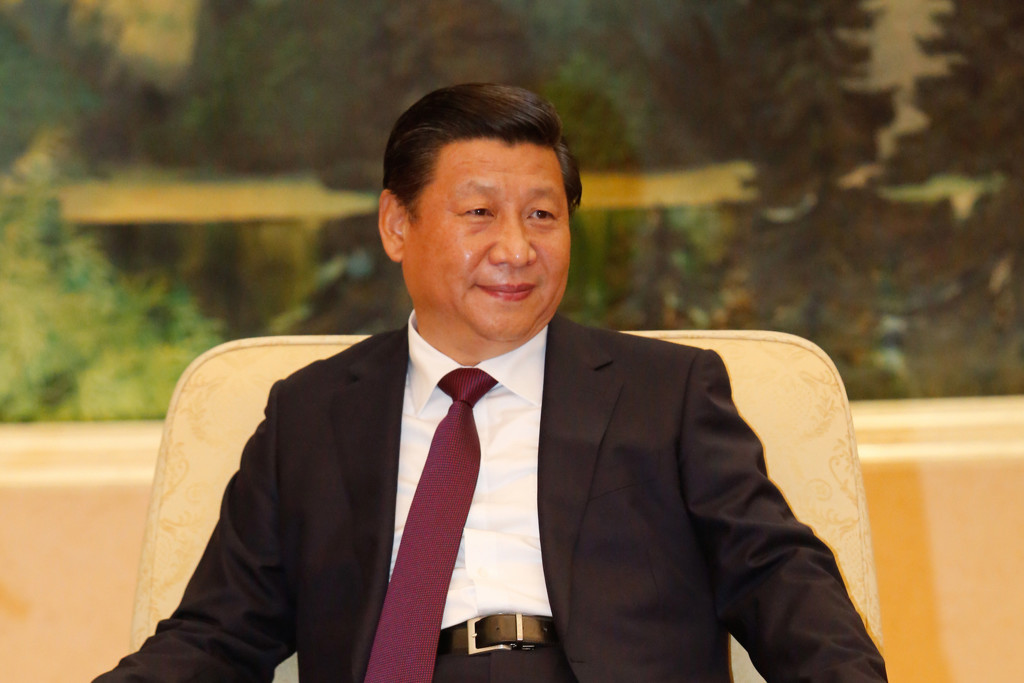

Not only known as the leader of the most populous country in the world, President Xi is also affectionately called “Daddy Xi”, with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sanctioned rap videos containing brilliant lyrics about his effectiveness as China’s top leader. This effusive praise, present in the CCP’s official publicity, has become commonplace across Chinese mass media. On February 18, the deputy director at China’s official Xinhua news agency wrote a stirring public poem about how President Xi Jinping has greatly inspired his creativity.

Xi has been the leader of China for nearly three years and his process of consolidating power has been expansive. He recently demanded “absolute loyalty” from all domestic and foreign media outlets, which must receive government permission before publishing online. Many had regarded President Xi as a potential reformer of China’s political system when he assumed office, but his drive to consolidate power and the rapid development of a low-scale cult of personality has prevented any positive change. Given China’s slowdown, Xi’s government is tightening control over the media and cultivating nationalism in order to offset inevitable dissatisfaction over a worsening economic climate. Rather than making critical reforms, his government is attempting to establish a Maoist-like form of ideological unity around Xi: a dangerous embrace of the past rather than a pursuit of much needed reform.

In the first decade of the 21st century many viewed China’s economic rise as unstoppable, but as of late, many significant structural issues are rapidly coming to light. Statistically, there is seemingly little to worry about as China still posted an official figure of 6.9% GDP growth. However, statistics in the country are often imprecise or have been significantly altered by the central government. A more accurate indicator is the Chinese stock market, which posted a steep decline resulting in a loss of 5 trillion dollars since last summer. The Chinese stock market is neither as large nor as developed as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), so its impacts on the total economy are not too severe. But, these losses serve as a harbinger for China’s future economic problems.

The most pressing issue is the significant dependence on investment for economic growth. Historically, China’s large investment to GDP ratio fueled development and expansion, but naturally with time, the number of investment-worthy projects has fallen. Yet with businesses fueled by government backed credit, the rate of investment is at a whopping 43% of GDP, and this has resulted in unused infrastructure, excess industrial capacity and a housing bubble. With debt-fueled investment flowing into questionable projects, there are concerns over whether this huge investment would yield appropriate returns to service high debt levels. Poorly chosen projects, such as empty cities in the middle of nowhere, cannot produce the appropriate amount of revenue to pay off the debt, meaning many individuals and companies are at risk of default.

As a result, China’s debt levels have quadrupled since 2007 and are at 282% of GDP. In addition, this past January exports fell by 11.2%, confirming the slowing industrial sector, and imports fell by 18.8%, indicating shrinking consumption. China needs to reduce its dangerously unsustainable dependence on investment and replace it with consumption if it wants to successfully transition into an economy like that of the US. However, consumption cannot increase in the short run without major reforms due to government incentives to invest combined with weakening exports, low income growth, income inequality and large numbers of impoverished people.

With these economic weaknesses becoming more apparent, it is no surprise that the CCP is engaged in policies of centralization and media control in an attempt to create ideological unity. China’s outward-projected image is that of a modern capitalist state with Shanghai as the poster-city. But in reality, China still retains a political economic system centered around a Maoist-communist, party-state hierarchy.

Mao used this centralized system to create a unified ideology and collective spirit to legitimize CCP control of China, but Deng Xiaoping, his successor, was more pragmatic, instead focusing on economic growth and welfare as a better tool to maintain party control. This turn was further entrenched with the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, which demonstrated the potential for the party to lose power.

However, the CCP is reverting away from Deng’s pragmatism. Their move toward centralization will mean continued, high levels of corruption as officials — unlike in the Maoist past — deal with wealthy businessmen and major projects. And corruption directly contributes to the explosion of unwise, debt-free investment in poor pet projects of party-state officials. Thus, embracing centralization will delay not only economic reforms but also essential reforms in governance.

While there is no perfectly clear solution to fix China’s problems, it is clear that attempting to recreate a Maoist unifying ideology is not a good option. Rather, China should not rest on its laurels of past achievements and instead face the sobering music that it must engage in a serious restructuring of the economy. A father needs to be able to do what is best, not necessarily what is most popular, and if “Daddy Xi” wants to live up to his popular reputation, it is best that he puts the state’s effort into reform and not Maoist ideological centralization.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.